Global Inequality of Opportunity

Living conditions are vastly unequal in different places in our world today. Today’s global inequality of opportunity means that what matters most for your living conditions is the good or bad luck of your place of birth. We look at how where you’re born is the strongest determinant of your standard of living, whether in life expectancy, income, or education.

This article was originally published more than three years ago. The data shown and discussed in the text are not always the latest available estimates. For more up-to-date data, see our interactive visualizations on incomes, child mortality, and education.

Living conditions are vastly unequal in different places in our world today. This is largely the consequence of the changes in the last two centuries: in some places, living conditions changed dramatically; in others, more slowly.

Our individual stories play out amidst these major global changes and inequalities, and it is these circumstances that largely determine how healthy, wealthy, and educated each of us will be in our own lives.1 Yes, our hard work and life choices matter. But as we will see in the data, these matter much less than the one big thing over which we have no control: where and when we are born. This single, utterly random, factor largely determines the conditions in which we live our lives.

Today’s global inequality is the consequence of two centuries of unequal progress. Some places have seen dramatic improvements, while others have not. It is on us today to even the odds and give everyone – no matter where they are born – the chance of a good life. This is not only right but, as we will see below, is also realistic. Our hope for giving the next generations the chance to live a good life lies in broad development that makes possible for everyone what is only attainable for a few today.

It strikes many people as inherently unfair that some people can enjoy healthy, wealthy, happy lives while others live in ill health, poverty, and sorrow. For them, it is the inequality in the outcomes of people's lives that matters. For others, it is the inequality in opportunity – the opportunity to achieve good outcomes – that is unfair. But the point of this text is to say that these two aspects of inequality are not separable. Tony Atkinson said it very clearly: “Inequality of outcome among today’s generation is the source of the unfair advantage received by the next generation. If we are concerned about equality of opportunity tomorrow, we need to be concerned about inequality of outcome today.”2

The extent of global inequality – it is not who you are, but where you are

Today’s global inequality of opportunity means that what matters most for your living conditions is the good or bad luck of your place of birth.

The inequality between countries that I am focusing on in this text is not the only aspect that needs to be considered. Inequalities within countries and societies – regional differences, racial differences, gender differences, and inequalities across other dimensions – can also be large, and are all beyond any individual’s control and unfair in the same way.

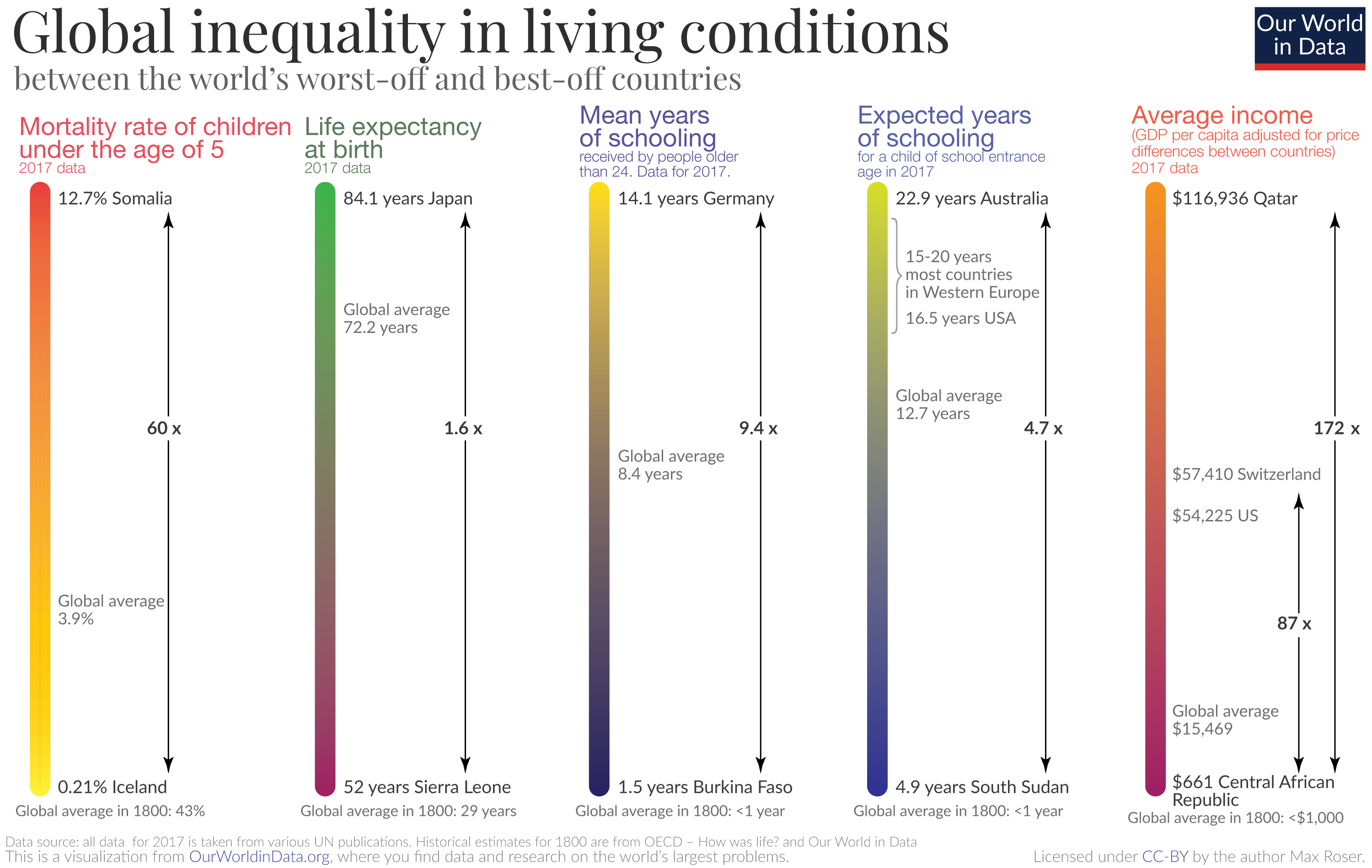

This visualization shows the inequality in living conditions between the worst and best-off countries in the world today in several aspects:

- Health: A child born in one of the countries with the worst health is 60 times more likely to die than a child born in a country with the best health. In several African countries, more than one out of ten children born today will die before they are five years old. In the healthiest countries of the world – in Europe and East Asia – only 1 in 250 children will die before he or she is 5 years old.

- Education: In the countries where people have the best access to education – in Europe and North America – children of school entrance age today can expect 15 to 20 years of formal education. In Australia, an outlier, school life expectancy is 22.9 years. Children entering school simultaneously in countries with the poorest access to education can only expect 5 years. And additionally, children tend to learn much less in schools in poorer countries, as we explained before.

- Income: If you look at average incomes and compare the richest country – Qatar, with a GDP per capita of almost $117,000 – to the poorest country in the world – the Central African Republic, at $661 – then you find a 177-fold difference. This is taking into account price differences between countries and therefore expressed in international-$ (here is an explanation). Qatar and other very resource-rich economies might be considered outliers here, suggesting that it is more appropriate to compare very rich countries without relying mostly on exports of natural resources. The US has a GDP per capita of int.-$54,225 and Switzerland of 57,410 international-$. This means the Swiss can spend in 1 month what people in the Central African Republic can spend in 7 years.

The inequality between different places is much larger than the difference you can make alone. When you are born in a poor place where every tenth child dies, you will not be able to get the odds of your baby dying down to the average level of countries with the best child health. In a place where the average child can only expect 5 years of education, it will be immensely harder for a child to obtain the level of education even the average child gets in the best-off places.

The difference is even starker for incomes. In a place where GDP per capita is less than $1,000, and the majority lives in extreme poverty, the average incomes in a rich country are unattainable. Where you live isn’t just more important than all your other characteristics, it’s more important than everything else put together.

You cannot get healthy and wealthy on your own – Societies make progress, not individuals

What is true for inequality across countries around the world today, is also true for change over time. What gives people the chance for a good life is when the entire society and economy around them changes for the better. This is what development and economic growth are about: transforming a place so that what was previously only attainable for the luckiest few comes into reach for most.

When everyone is sick, everyone is sick

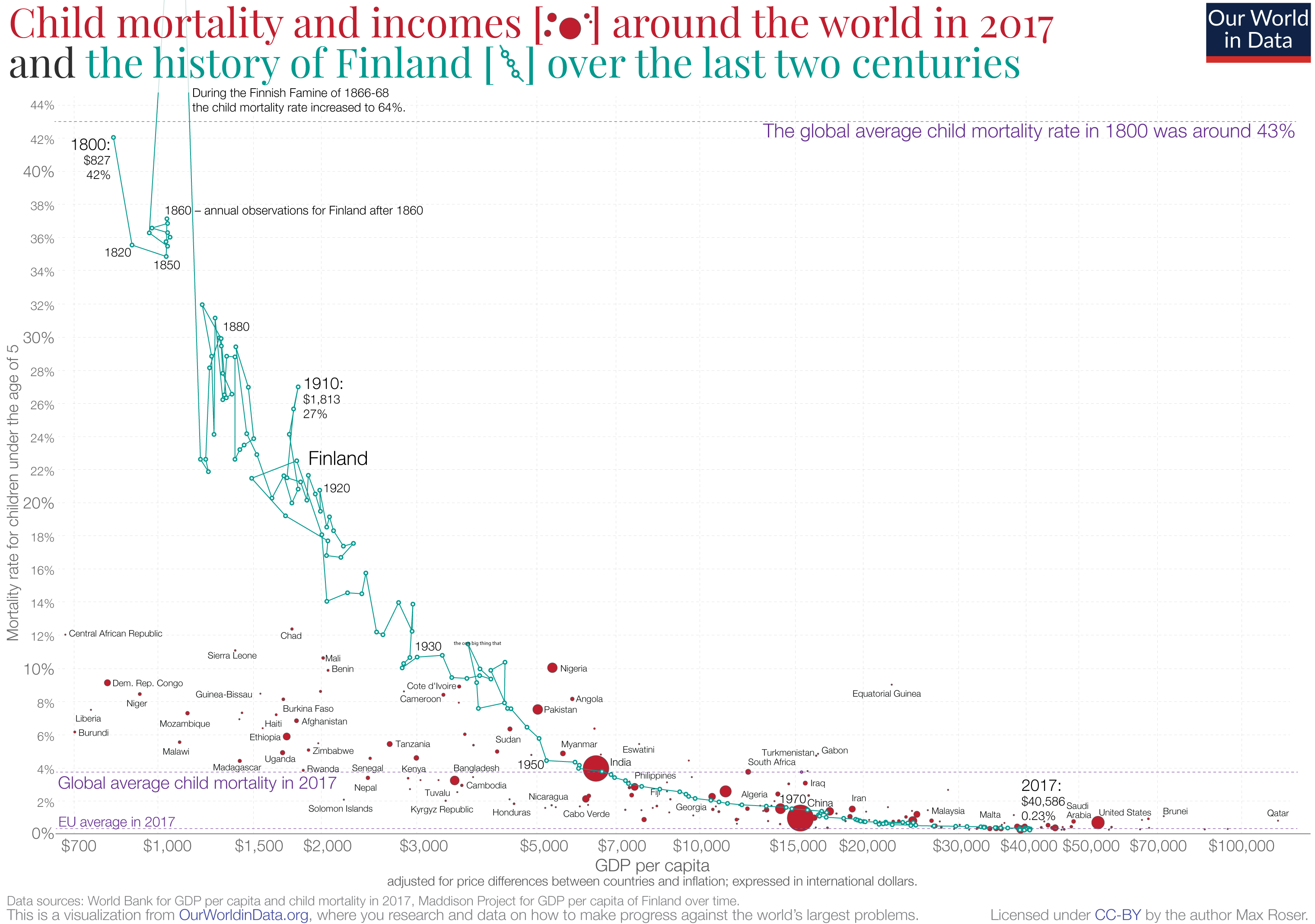

The blue line in this visualization shows this transformation of Finland, a country where people today are among the healthiest and richest in world history.

The data point in the top left corner describes life in Finland back in 1800 (a time when the country was not yet autonomous or independent). Of all children born that year, 42% died in the first five years of their lives. And the average income in Finland was extremely low: GDP per capita was only $827 per year (this is adjusted for price increases to keep the purchasing power comparable to today). And similarly, even basic education was not available for most.

A society where almost half of all children died was not unusual: it was similarly high in humanity’s history until recently. The dashed purple line in the chart shows that around the world in 1800, a similarly high share of children died before their fifth birthday. At that time, there was little global inequality; life was short everywhere, and no matter where a child was born, chances were high that he or she would die soon.

And just as there was little inequality in mortality and health between different places worldwide, there was little inequality within countries. The health of the entire society was bad. We have data on the mortality of the English aristocracy from 1550 onwards. Aristocrats died just as early as everyone else.3 Their life expectancy was below 40 years too. Before broader social development, even the most privileged status within society would not give you the chance for a healthy life. You just cannot be healthy in an unhealthy place.

Development and global inequality

After two centuries of slow, but persistent transformation, Finland is today one of the healthiest and wealthiest places in the world. It wasn’t smooth progress – during the Finnish Famine in the 1860s, the mortality rate increased to over half – but gradually, child health improved, and today the child mortality rate is 0.23%. Within two centuries, the chances of a Finnish child surviving to the first five years of life increased from 58% to 99.77%.

The same is true for income. Back in 1800, global inequality between countries was much lower than it is today. Even in those countries that are today the richest in the world, the majority of people lived in extreme poverty until recently. Finland was no exception.

The red bubbles in the same chart show child mortality and income today. It is the same data that we discussed above in the discussion on the extent of global inequality today, but now you see the data for all the world’s countries, not just the worst- and best-off.

Until around 1800, today’s best-off places were as poor as today’s worst-off places, and child mortality was even worse. All were in the top-left corner of the chart. What created the global inequality we see today were the large cross-country differences in improvements in health and economic growth over the last two centuries. Angus Deaton referred to this as the ‘Great Escape’. He wrote a book about it with this title, in which he chronicles how some parts of the world escaped the worst poverty and disease, while others lagged.

Without looking at the data, it is impossible to understand just how dramatically the prosperity and health of a society can be transformed. The health and prosperity in the past were so bad that no one in Finland could have imagined living the life that is today the reality for the average person in Finland.

Development caused inequality between places and between generations

Even the countries where health and access to education are worst today have made progress in these dimensions. In the first chart of this text, I added the estimates for the global average for each dimension two centuries ago underneath each scale. In terms of health, even today’s worst-off places are faring better than the best-off places in the past. Here is the evidence for life expectancy and here for child mortality.

And just as there is almost no overlap between the distributions of income in today’s poor and rich countries, there is also almost no overlap between the distribution of income in a rich country today and that of the same country in the past.

The fact that these transformations improved the living conditions of entire societies so dramatically means that it’s not just where you are born that matters for your living conditions, but also the time when you were born. Children with a good chance of survival are not just born in the right place, but also at the right time. In a world of improving health and economic growth, all of us born in the recent past have had much better chances of good health and prosperity than all who came before us.

Conclusion

As Atkinson said, “If we are concerned about equality of opportunity tomorrow, we need to be concerned about inequality of outcome today.”

The global inequality of opportunity in today’s world results from global inequality in health, wealth, education, and the many other dimensions that matter in our lives.

Your living conditions are much more determined by what is outside your control – the place and time that you are born into – than by your effort, dedication, and the choices you have made in life.

The fact that it is the randomness of where a child is born that determines his or her chances of surviving, getting an education, or living free of poverty cannot be accepted. We have to end this unfairness so that children with the best living conditions are just as likely to be born in Sub-Saharan Africa as in Europe or North America.

We know that this is possible. This is what the historical perspective makes clear. Today Finland is in the bottom right corner of the chart above: one of the healthiest and richest places on the planet. Two centuries ago, Finland was in the top left: as poor as today’s poorest countries and with a child mortality rate much worse than any other place today.

The inequality that we see in the world today is the consequence of unequal progress. Our generation has the opportunity – and responsibility, I believe – to allow every part of the world to develop and transform into a place where health, access to education, and prosperity are a reality.

There is no reason to believe that what was possible for Finland – and all other countries in the bottom right, which today are much healthier and wealthier than they were two centuries ago – should not be possible for the rest of the world. Indeed, as shown by the massive reduction in global child mortality between 1800 and 2017 – from a global average of 43% to 3.9%, as indicated by the horizontal dashed lines – much of the world is well on its way.

Both the progress of the past and the vast inequality worldwide show what is possible for the future. The William Gibson quote, "The future is already here, it is just unevenly distributed", has been true for the entire course of improving living conditions and was a good guide for what is possible for the future everywhere.

We at Our World in Data focus on “data and research to make progress against the largest global problems” (this is our mission), and global inequality is one of them. Once we know what is possible, we surely cannot accept today’s brutal reality that it is the place where a child is born that determines their chances for a wealthy and healthy life.

Endnotes

There is a large research literature that aims to differentiate the outcomes of inequality driven by individual life choices from the inequality caused by the individual's circumstances over which they have no control, like their place of birth, sex, race, and many other aspects. See, for example, Roemer (2000) – Equality of Opportunity, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Page 11 in Anthony B. Atkinson (2015) – Inequality What Can Be Done?. Published by Harvard University Press. https://www.tony-atkinson.com/new-book-inequality-what-can-be-done

The data on the health of the English aristocrats was published in Thomas Hollingsworth (1964) – “The demography of the British peerage” Population Studies 18(2), Supplement, 52–70. For the comparison with the general population, see Bernard Harris (2004) – “Public health, nutrition, and the decline of mortality: The McKeown thesis revisited,” Social History of Medicine 17(3): 379–407. https://academic.oup.com/shm/article-abstract/17/3/379/1718691 Even in those poor pre-modern societies in which there was a health gradient between better-off and worse-off parts of society, the healthiest did not come remotely close to the average in a healthy society today.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Max Roser (2019) - “Global Inequality of Opportunity” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/global-inequality-of-opportunity' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-global-inequality-of-opportunity,

author = {Max Roser},

title = {Global Inequality of Opportunity},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2019},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/global-inequality-of-opportunity}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.