Does population growth lead to hunger and famine?

Many countries with high population growth have recently managed to substantially decrease levels of hunger.

This post is the first of a pair of posts looking at the relationship between famines and population growth. Here, we consider whether population growth causes famine and hunger. In a second post, we look at the demographic impacts of famines, particularly the extent to which famines may “check” population growth.

Modern Malthusians

It’s no good blaming climate change or food shortages or political corruption. Sorry to be neo-Malthusian about it, but continuing population growth in this region makes periodic famine unavoidable... Many of the children saved by the money raised over the next few weeks will inevitably be back again in similar feeding centres with their own children in a few years time1.

It is not uncommon to see arguments along the lines of this quote from Sir Jonathon Porritt, claiming that famines are ultimately caused by overpopulation. Porritt – former director of “Friends of the Earth” and also the former chairman of the UK Government’s Sustainable Development Commission – was talking about the 2011 famine in Somalia that went on to kill roughly 250,000 people.2 He seems certain that the rapid population growth witnessed in East Africa had made famine there “unavoidable”.

There is something compelling about this logic: a finite land area, with a limited ‘carrying capacity’, cannot continue to feed a growing population indefinitely. From such a perspective, the provision of humanitarian aid to famine-afflicted countries, however well intended, represents only a temporary fix. In this view, it fails to address the fundamental issue: there simply are too many mouths to feed.

As mentioned in the quote, this suggestion is commonly associated with the name of Thomas Robert Malthus, the English political economist writing at the turn of the nineteenth century. Malthus is famous for the assertion that in the absence of “preventative checks” to reduce birth rates, the natural tendency for populations to increase – being “so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man” – ultimately results in “positive checks” that increase the death rate. If all else fails to curb population, “gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world”.3

But does the evidence support this idea? Here, we look into the relationship between population growth and famine, as well as that between population growth and hunger more generally.

Does population growth cause famine?

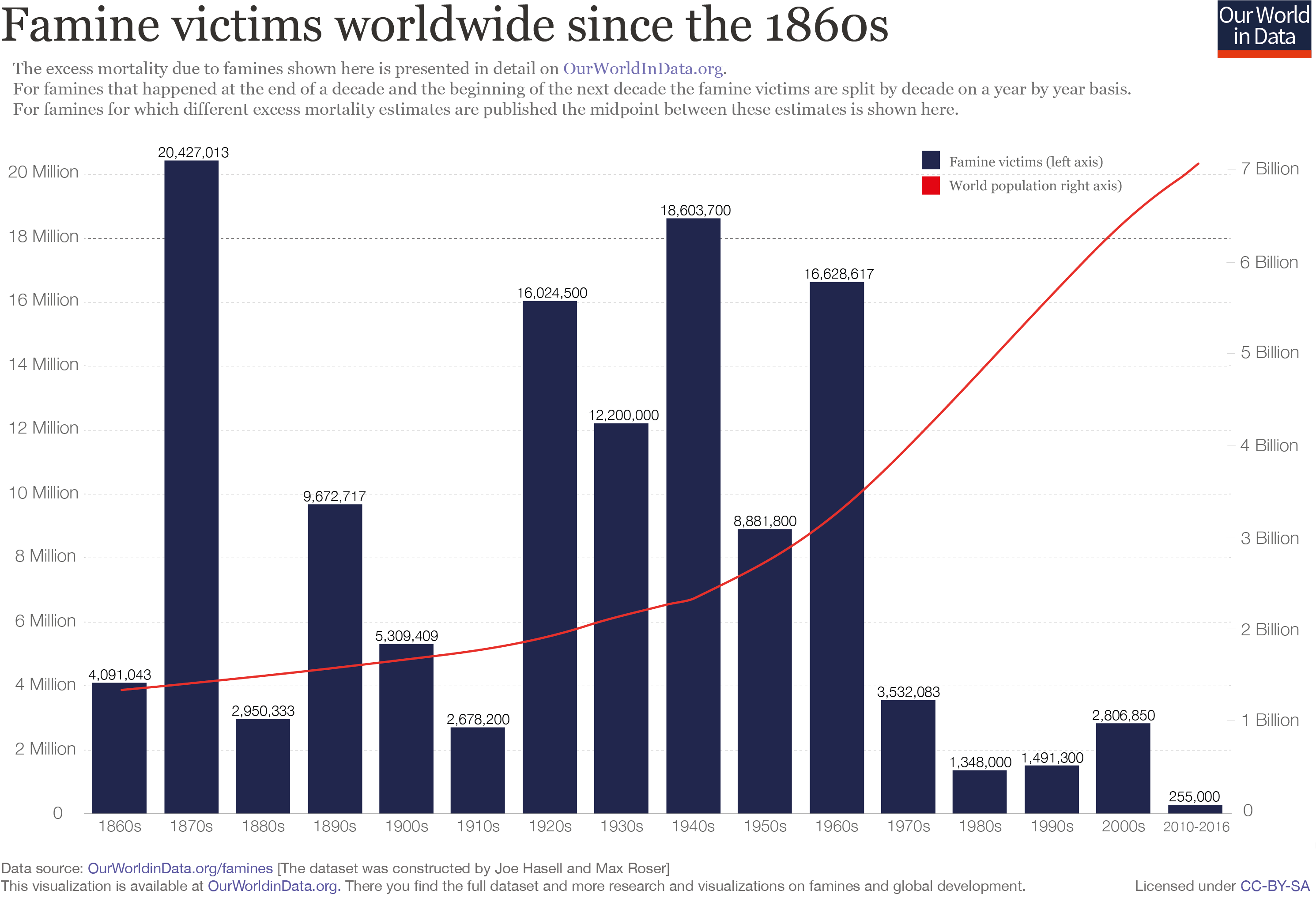

This chart compares the number of famine deaths per decade – based on our famine dataset – with the world population over the same period.

Looking at the world as whole, it is very difficult to square Malthus' hypothesis with the simple but stark fact that, despite the world's population increasing from less than one billion in 1800 to more than seven billion today, the number of people dying due to famine in recent decades is only a tiny fraction of that in previous eras.

We might naturally think that the explanation for this trend lies in increasing agricultural production. Indeed, the food supply per person has consistently increased in recent decades, as we can see in the interactive line chart shown. The large increase in global population is being met with an even greater increase in food supply (largely due to increases in yields per hectare).

However, looking at the issue in this way is too simple. As we discuss in our entry on famines, insufficient aggregate food supply per person is just one factor that can bring about famine mortality. Contemporary famine scholarship tends to suggest that insufficient aggregate food supply is less important than one might think and instead emphasizes the role of public policy and violence: in most famines of the 20th and 21st centuries, conflict, political oppression, corruption, or gross economic mismanagement on the part of dictatorships or colonial regimes played a key role.4

The same also applies to the most acutely food-insecure countries today.5

It is also true of the 2011 famine in Somalia referred to above, in which food aid was greatly restricted, and in some cases diverted, by militant Islamist group al Shabaab and other armed opposition groups in the country.6

Famine scholar Stephen Devereux of the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, summarizes the trajectory of famines over the 20th century as follows: "The achievement of a global capacity to guarantee food security was accompanied by a simultaneous expansion of the capacity of governments to inflict lethal policies, including genocidal policies often involving the extraction of food from the poor and denial of food to the starving."7

Thus, all in all, the recent history of famine mortality does not fit the Malthusian narrative particularly well. Firstly, contrary to what Malthus predicted for rapidly increasing populations, food supply per person has – in all regions – increased as populations have grown. Secondly, famines have not become more, but less frequent. Thirdly, in the modern era, the occurrence of major famine mortality and its prevention is something for which politics and policy seem to be the more salient triggers.

Does population growth increase hunger?

Global picture

Famines tend to be thought of as acute periods of crisis and are, in that sense, to be distinguished from more chronic manifestations of hunger that may, in some places, represent “normal” circumstances despite being responsible for large numbers of deaths.8

Given the typically political nature of outbreaks of such famine crises, it may make more sense to look for the effect of population growth on the longer-term trends of hunger and malnutrition.

But again, at the global level, we know that population growth has been accompanied by a downward trend in hunger. As we discuss in our entry on hunger and undernourishment, in recent decades, the proportion of undernourished people in the world has fallen, and, although more muted, this fall is also seen in the absolute number. The number of people dying globally due to insufficient calorie or protein intake has also fallen, from almost half a million in the 1990s to roughly 300,000 in the most recent data, as shown in the visualization.

Within countries

We can also look at the experiences of individual countries rather than just at the global level. Do those countries with particularly high population growth rates find it harder to adequately feed its population?

In order to get some idea about this, we can compare countries' Global Hunger Index (GHI) scores with their population growth rates. GHI is a composite measure out of 100 that combines four indicators: undernourishment, child wasting, child stunting, and child mortality.9

The first scoring was conducted in 1992 and repeated every eight years, with the most recent being carried out in 2017. The score is based on data collected in the years leading up to the scoring year and as such, reflects the hunger levels in this period rather than solely capturing conditions in the year itself. All the countries for which there was GHI data available between 1992 and 2017 are shown in the three charts.10 Crucially, this excludes a number of very food-insecure countries , including the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, and Somalia, which have also seen high levels of population growth.11 This should be borne in mind when interpreting the following results.

Of the countries for which we do have GHI data, it is clear that those with higher levels of hunger have also tended to have had higher population growth over the last 25 years.12

It is important to see though that among the countries for which we have GHI scores in both 1992 and 2017, the level of hunger went down in all but one – Iraq. Over the same period population went up in almost every case. Moreover, those countries that experienced higher levels of population growth in fact saw a bigger drop in their GHI score over this period.13

The countries that saw high population growth over this period started with higher levels of hunger in 1992. So what we are seeing here is that countries are converging towards lower levels of hunger: it fell quickest in countries with the highest levels of hunger.

So, whilst countries that experience hunger do tend to have high levels of population growth, the idea that population growth necessarily leads to increased hunger is clearly mistaken: many countries with high population growth have recently managed to decrease levels of hunger substantially.

Population growth does not make famine inevitable

Environmental degradation, including climate change, does pose a threat to food security, and the growth of human populations has undoubtedly exacerbated many environmental pressures. However, this represents only one aspect of the complex explanation of why so many people suffer and die from undernourishment today despite there being adequate food available for consumption globally.14

“Malthusian” explanations of famine and hunger thus fall short for the following reasons, the evidence for which we reviewed above:

- Per capita food supply has increased as populations have grown, largely due to increasing yields.

- Famine deaths have decreased, not increased, with population growth.

- Food scarcity has played a smaller role in famines than suggested by the Malthusian narrative. It ignores other factors like conflict, poverty, access to markets, healthcare systems, and political institutions.

- Population growth is high where hunger is high, but that does not mean that population growth makes hunger inevitable. On the contrary, we see that hunger has fallen fastest in countries with high population growth.

If we want to put an end to hunger, we need to understand the diverse causes that bring it about. Oversimplifications that mistakenly see hunger and famine as an inevitable consequence of population growth do not contribute to this end.

Endnotes

Who would have thought it? Population growth and famine would appear to be linked! Blog entry from www.jonathonporritt.com, dated 11/07/2011. Accessed 19 Jan 2018. Emphasis added

The excess mortality estimate is taken from the World Peace Foundation list of famines.

Malthus T.R. 1798. An Essay on the Principle of Population. Chapter VII, p 44.

See, for instance, de Waal, A. The end of famine? Prospects for the elimination of mass starvation by political action, Political Geography, 62:2008

The threat of famine in Yemen, South Sudan, and Nigeria are all the direct consequence of conflict, and the drought in Somalia arrives after decades of conflict and political instability. See FEWS.net for more details.

Seal, A., & Bailey, R. (2013). The 2011 Famine in Somalia: lessons learnt from a failed response? Conflict and Health, 7, 22. http://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-7-22. As the authors note, this was in part due to concern on the part of humanitarian organizations that they would be contravening US government sanctions. Furthermore, both the US and the EU significantly reduced humanitarian spending in the country in the run-up to the famine.

Devereux, S. Famine in the Twentieth Century. IDS working paper 105, 2000.

de Waal, 2018 defines famine as “a crisis of mass hunger that causes elevated mortality over a specific period of time”. Note that the official IPC classification system used by the UN for famine declarations just looks at total (undernourishment-related) death rates in absolute terms rather than relative to any non-crisis reference level. This contrasts somewhat with the typical ex-ante famine assessment in which excess mortality is estimated by factoring out the counterfactual death rate – however high.

More information on these individual indicators, including their definitions, can be found in our entry on Hunger and Undernourishment.

Population data was taken from the World Bank from 1992 to 2016. Note that GHI is typically not collected for wealthy countries. Below a score of 5, GHI gets bottom coded as '<5'. Of the 95 countries for which we have data in both years, none of them began bottom-coded, but five moved into this range by 2017. In the following analysis, we replaced these bottom-coded observations with a GHI of 2.5. However, the key results are robust to omitting these countries altogether. As a robustness check, we also conducted the analysis on the prevalence of undernourishment separately (one of the four components of GHI). The key results remained unchanged.

These three countries would be situated in the top quarter of our sample in terms of population growth, with DRC and South Sudan roughly in the top decile.

Statistically significant at the 1% level, even when controlling for GDP per capita in 2016 (using World Bank PPP data)

This relationship is significant at the 1% level. The relationship is stronger (both in magnitude and significance) controlling for GDP per capita (using World Bank PPP data)

World food supply per person is higher than the Average Dietary Energy Requirements of all countries. See our page on Food Supply for more details.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Joe Hasell (2018) - “Does population growth lead to hunger and famine?” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth-and-famines' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-population-growth-and-famines,

author = {Joe Hasell},

title = {Does population growth lead to hunger and famine?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2018},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth-and-famines}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.