Women have made major advances in politics — but the world is still far from equal

Women have gained the right to vote and sit in parliament almost everywhere. But they remain underrepresented, especially in the highest offices.

How much progress has been made toward women’s political equality? How far do we still have to go?

In this article, I show global data on women’s political rights and representation.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, women did not have the right to vote or sit in parliaments, and only very few — of royal descent — led their countries.

Women became much better represented in the later 20th century, gaining the right to vote and seats in parliaments in almost all countries, and making it to their country’s highest political office more frequently.

However, the data also shows that this progress has been uneven and limited: women still do not have the right to vote in a handful of countries; women parliamentarians continue to be a small minority in most countries; and women political leaders remain rare.

Let’s look at how far we have come and what remains to be done.

Women have gained the right to vote in almost all countries

A fundamental political right is choosing one’s political representatives in elections. Until recently, women did not have this right to vote in countries’ elections.

Using data from political scientist Svend-Erik Skaaning and colleagues, the chart shows that neither women nor men had the universal right to vote almost anywhere until the middle of the 19th century.

Then a gap in political participation opened: men gained voting rights in some countries, while women remained mostly excluded. New Zealand became the first exception to this, where women gained the universal right to vote in 1893.

The gap between women and men further opened in the early 20th century, as women gained the right to vote in more countries, but men’s voting rights spread even farther. By the beginning of World War II, men had the right to vote in 1 out of 3 countries, while women only had the right to vote in 1 out of 6 countries.

The gap rapidly closed in the decades after World War II, when the voting-rights discrimination against women ended in many countries, and both women and men gained the right to vote in many others.

Today there are no countries that formally discriminate between men and women regarding the right to vote. In 2006, Kuwait was the last country that extended the right to vote to women. The corresponding area in the chart therefore disappears in recent years.

However, six countries and territories still have no right to vote for women or men: Brunei, Gaza, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, and the United Arab Emirates.

When it comes to voting rights, what is needed is more of a general expansion of rights rather than ending discrimination against women.

On this map, you can see the voting rights in each country. You can explore how each country changed over time by moving the time slider.

The share of women in parliament has increased a lot in many countries

Another crucial mark of political equality is women’s ability to represent their fellow citizens.

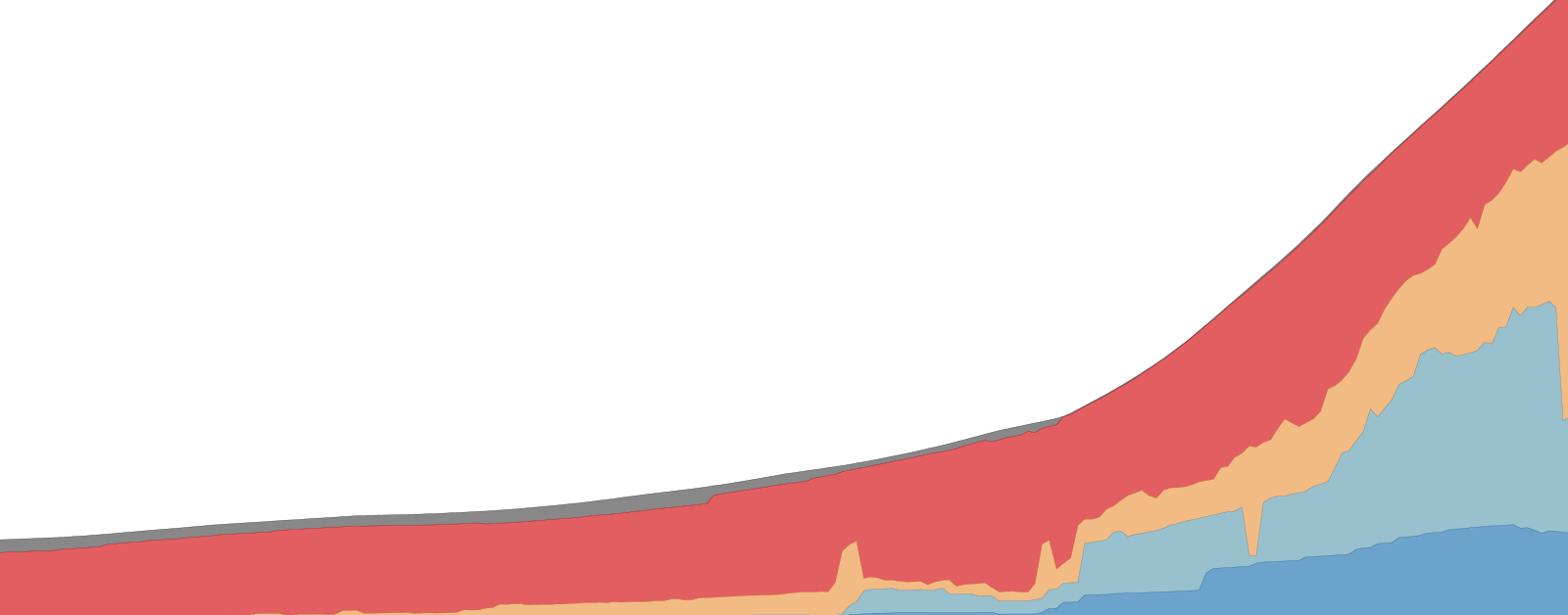

This chart, using data from the Varieties of Democracy project (V-Dem), shows that women were completely excluded from national parliaments in the early 20th century. No woman was among the parliamentarians in any of the countries that had a legislature.

Women entered the first parliament in 1907, making up almost 10% of Norway’s legislature.

After very limited progress in the first half of the 20th century, women made it into many more parliaments in its second half.

The process sped up in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In 2008, the Rwandan parliament became the first to have more than 50% women — the first women-majority parliament. That year, another handful of countries had between 40 and 50% women parliamentarians.1

However, progress in women’s political representation has been limited and uneven. Only in a few dozen countries do women make up around half of all representatives. In many, women parliamentarians are a small minority. In a few, there are none.

This means that many countries must double or triple the number of women in their parliaments to achieve equal representation.

On this map, you can explore the share of women in parliament for each country and year.

Women have led many countries, but most political leaders are still men

Women’s political representation in parliament is important, but so is their representation in a country’s highest political office.

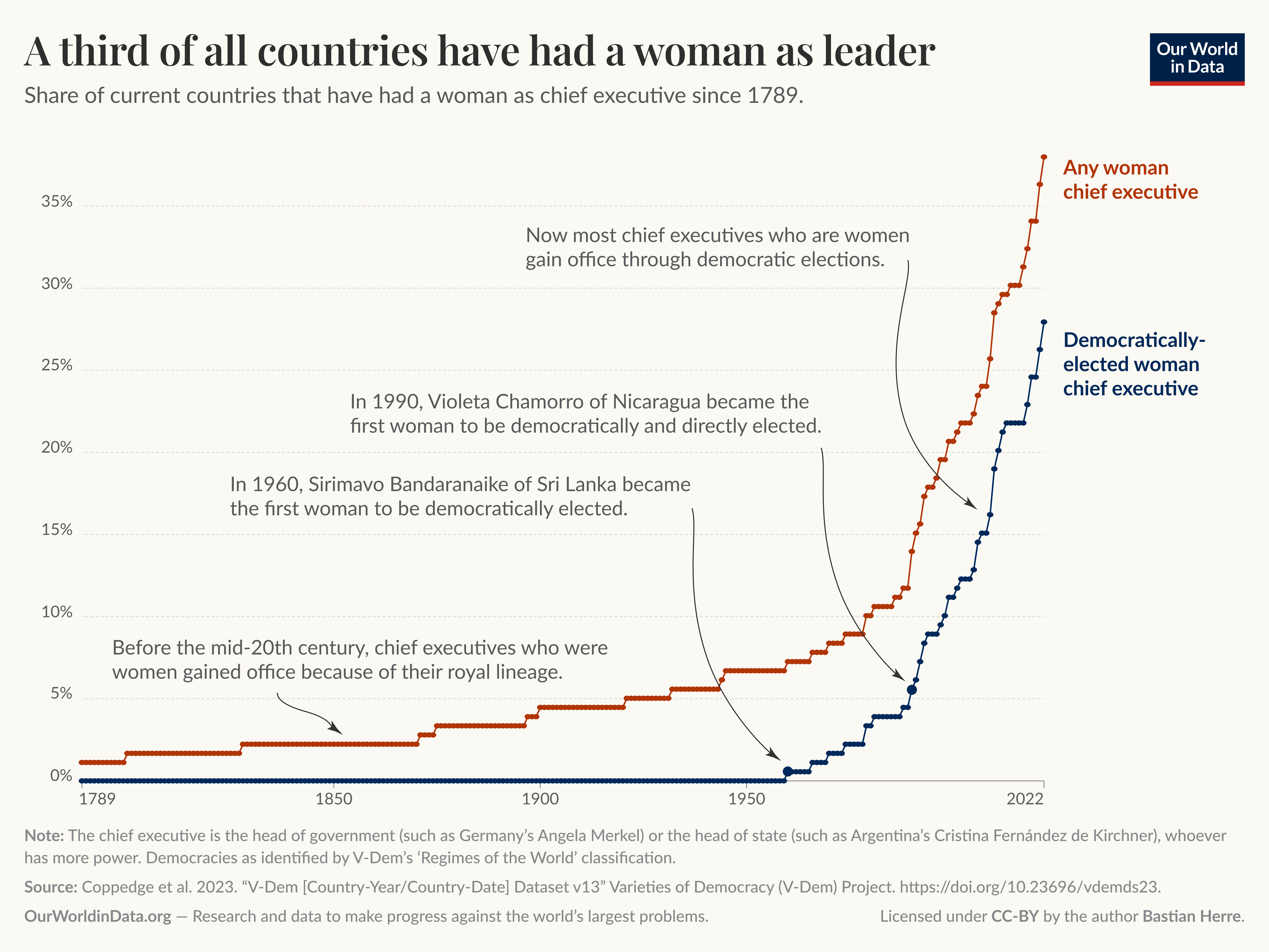

The next chart, again using V-Dem data, shows that a third of all current countries have had a woman as chief executive. “Chief executive” means the head of state or head of government, depending on who has more power.

Until the middle of the 20th century, few countries had political leaders that were women. These were monarchs, who rose to their positions because of their royal lineage.

Since then, many more countries have had a woman as chief executive, a trend mostly driven by democracies. This began with Sri Lanka’s democratically elected Sirimavo Bandaranaike in 1960, and has also included democratic leaders that were directly elected by their citizens (instead of being elected through elected representatives), with the first being Nicaraguan president Violeta Chamorro in 1990.

The chart shows that this trend has accelerated recently. More than a third of countries have now had a woman leader, and more than a quarter of them have had a democratically elected one.

The next chart shows how underrepresented women nonetheless are in the highest office. At any given point in time, almost all political chief executives still have been men.2

Prominent exceptions to men’s monopoly on countries’ highest offices include India’s Indira Gandhi, Bangladesh’s Sheikh Hasina, and Germany’s Angela Merkel, the heads of government of their respective countries; and Russia’s Catherine II, Liberia’s Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and Argentina’s Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who were their countries’ head of state.

Overall, we see a slight increase in the share of countries led by women in the last three decades.3 However, it is much smaller than the share of countries that ever had a woman as chief executive, with women still outnumbered by men by more than 9 to 1.

To reach equal political representation, the world would need more than five times as many women as political leaders.

The map allows you to explore the specific countries and years that saw women chief executives.

Much progress, but many shortcomings remain

The world has come a long way towards political equality.

Only a century ago, women were disenfranchised and excluded from their country’s most important political institutions virtually everywhere. Now they are voting in almost all countries, they represent their fellow citizens in legislatures and sometimes lead their countries.

But, the world still has far to go towards full equality.

In a few countries, both women and men still do not have the right to vote. Women are far outnumbered by men in their national legislatures. And very few women make it to their country’s highest office.

Importantly, women’s political equality is more than participation and representation in politics. It also means that women enjoy civil liberties, such as the freedom of movement, can fully participate in civil society, and have the same political power. While women have made much progress there as well, there is still much left to be done.

The data shows that change is possible. It is on us to continue the past trends and create political systems in which women truly have the same political rights and say.

Acknowledgments

I thank Pablo Arriagada, Edouard Mathieu, Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Fiona Spooner for their very helpful comments and ideas on this text.

Keep reading at Our World in Data

Women’s Rights

How has the protection of women’s rights changed over time? How does it differ across countries? Explore global data and research on women’s rights.

200 years ago, everyone lacked democratic rights. Now, billions of people have them

Half of all countries are democracies. But how many people enjoy democratic rights?

Endnotes

The countries with between 40 and 50% women parliamentarians were Argentina, Cuba, Finland, and Sweden.

We also have charts on heads of government and state by country, respectively. Women were almost absent among heads of government until the second half of the twentieth century, while women were a bit more common among heads of state. Women are also underrepresented in slightly less senior political offices: ministerial positions.

This looks similar when we look at the number of people living in countries in which a woman is chief executive.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Bastian Herre (2024) - “Women have made major advances in politics — but the world is still far from equal” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/women-political-advances' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-women-political-advances,

author = {Bastian Herre},

title = {Women have made major advances in politics — but the world is still far from equal},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2024},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/women-political-advances}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.