Causes of Death

What are people dying from?

This question is essential to guide decisions in public health, and find ways to save lives.

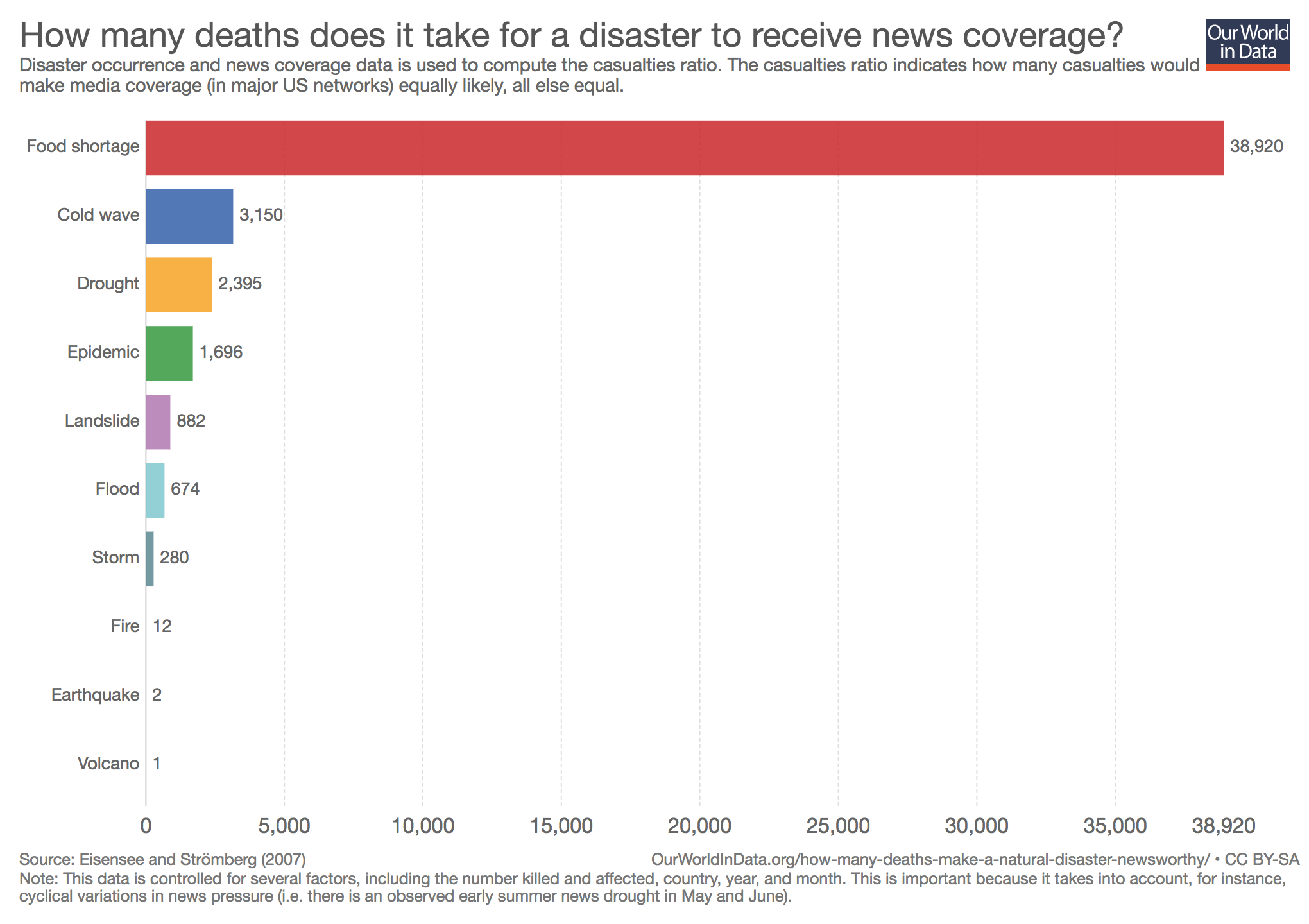

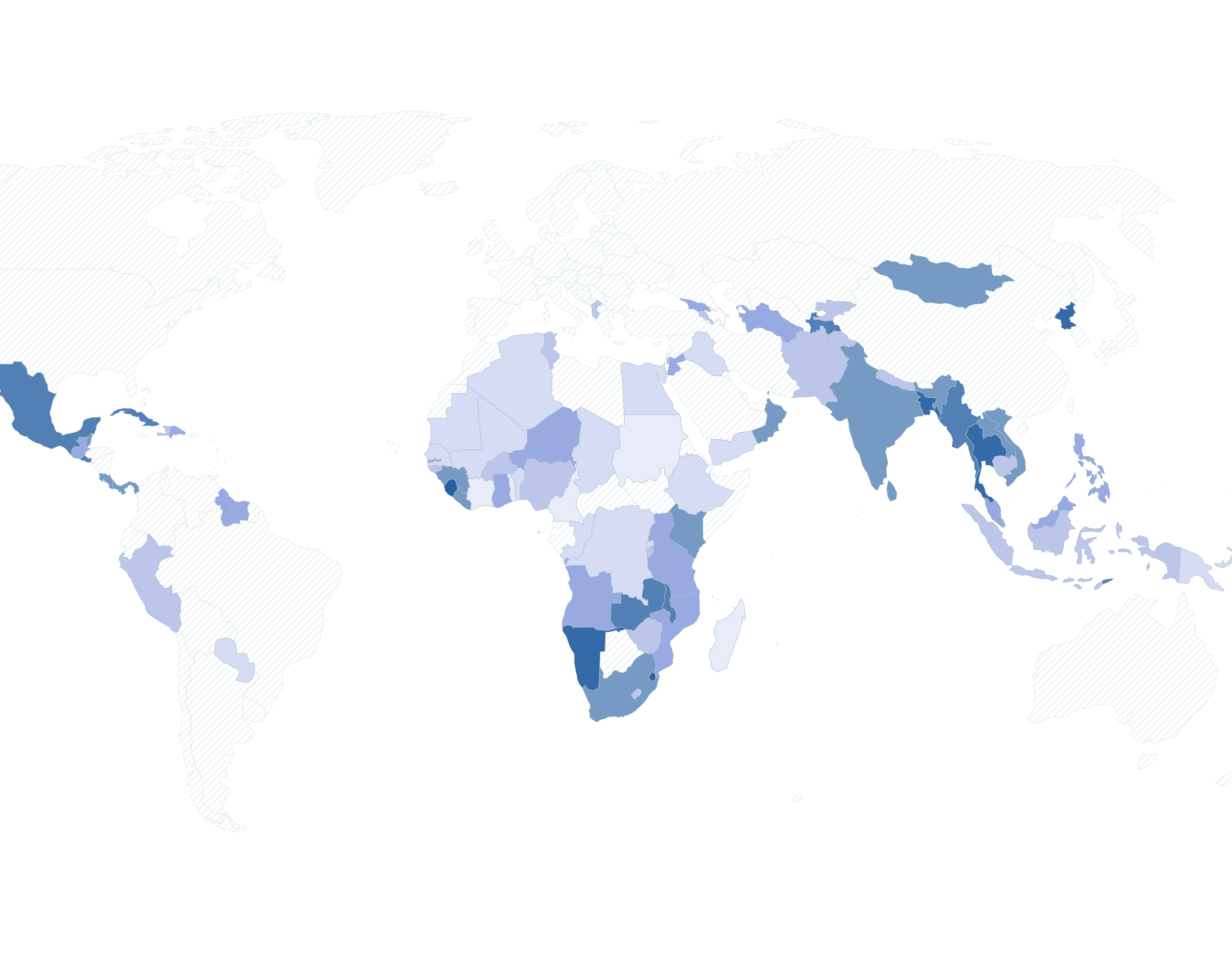

Many leading causes of death receive little mainstream attention. If news reports reflected what children died from, they would say that around 1,400 young children die from diarrheal diseases, 1,000 die from malaria, and 1,900 from respiratory infections – every day.

This can change. Over time, death rates from these causes have declined across the world.

A better understanding of the causes of death has led to the development of technologies, preventative measures, and better healthcare, reducing the chances of dying from a wide range of different causes, across all age groups.

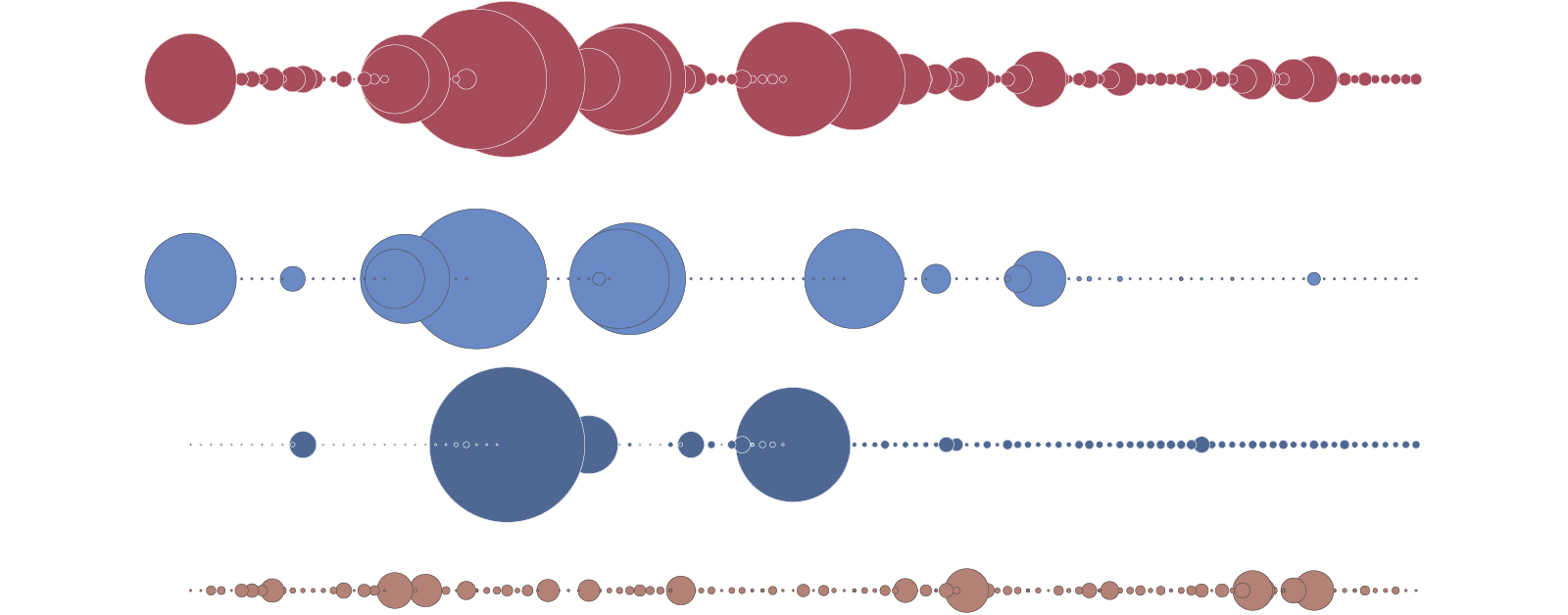

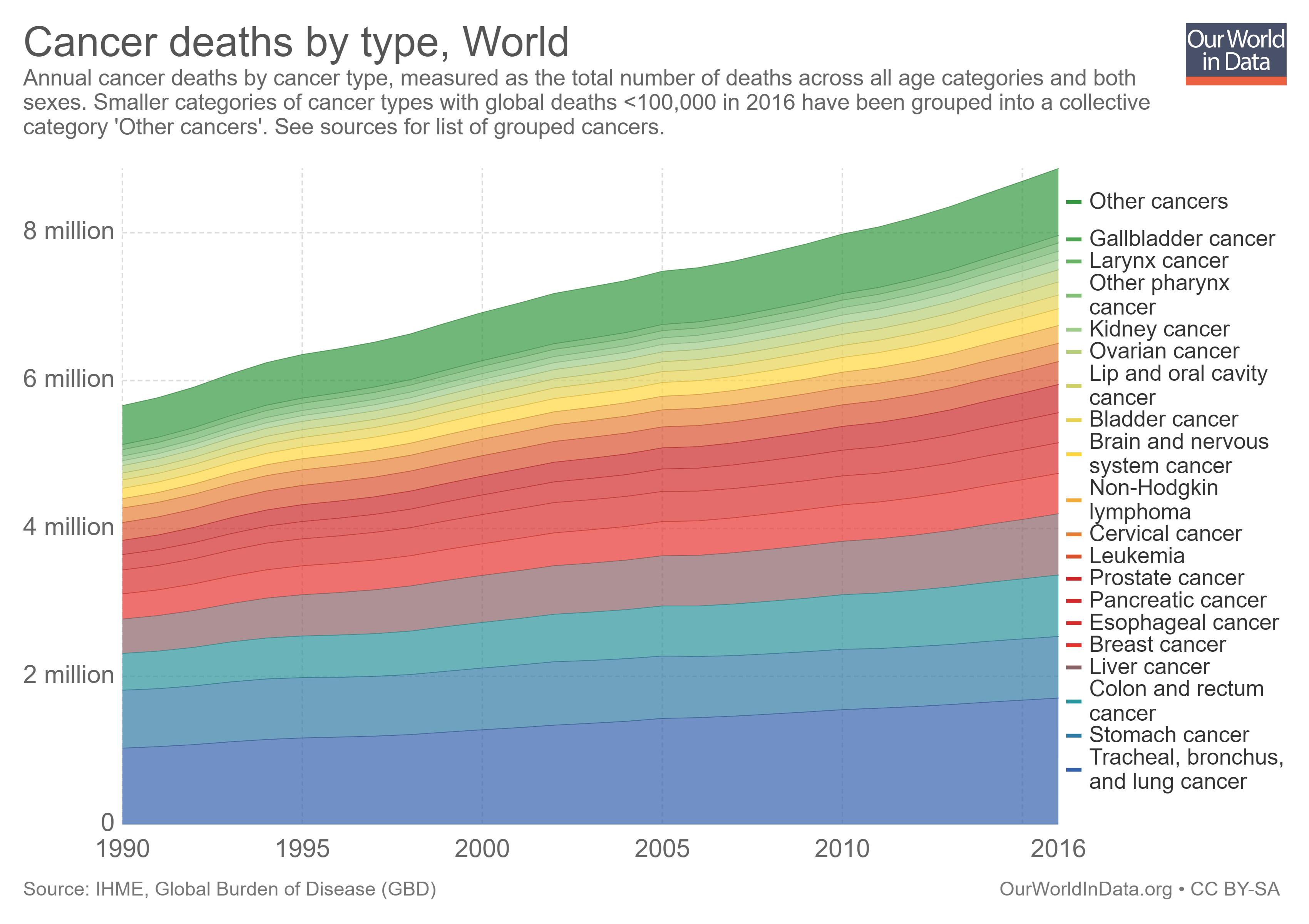

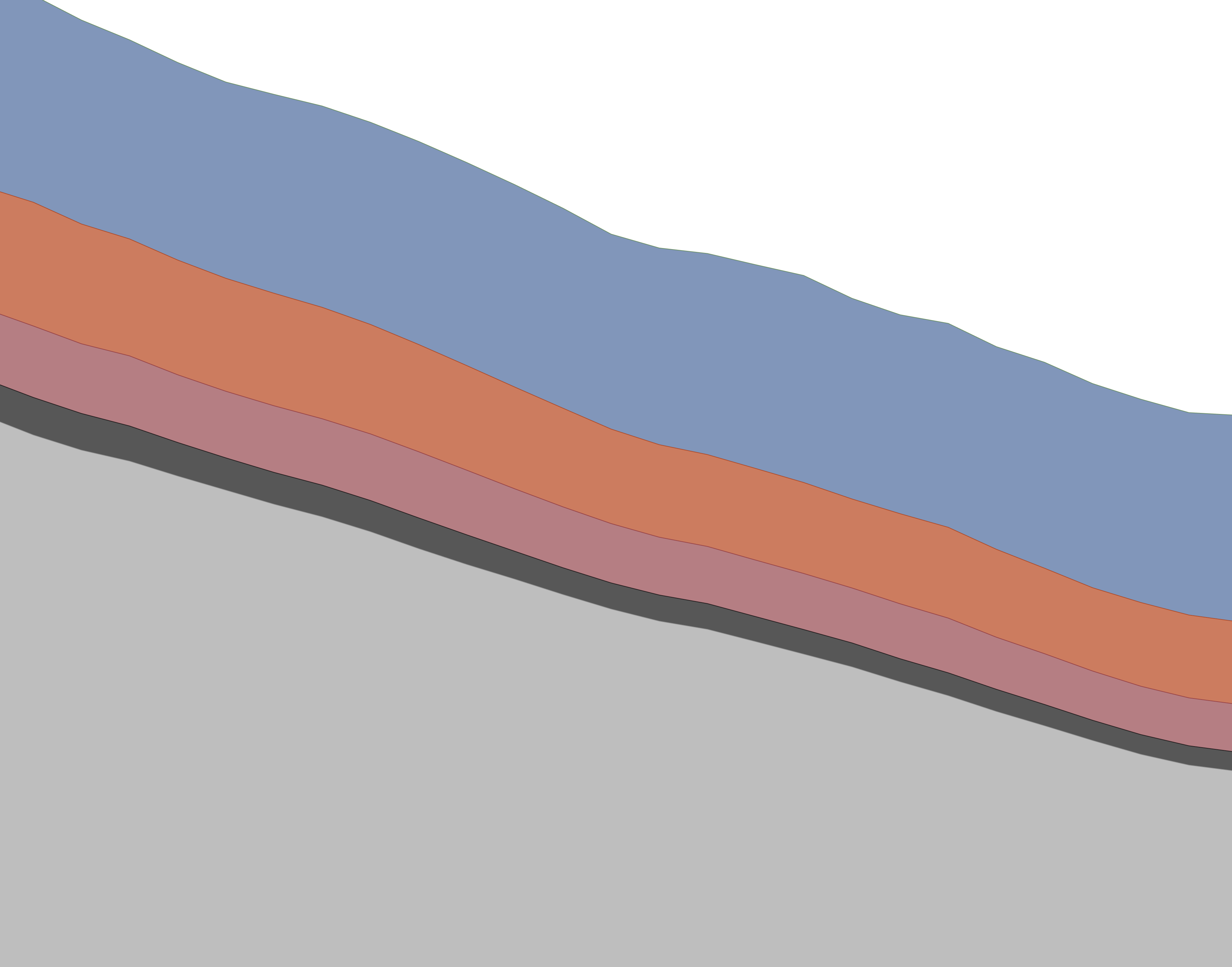

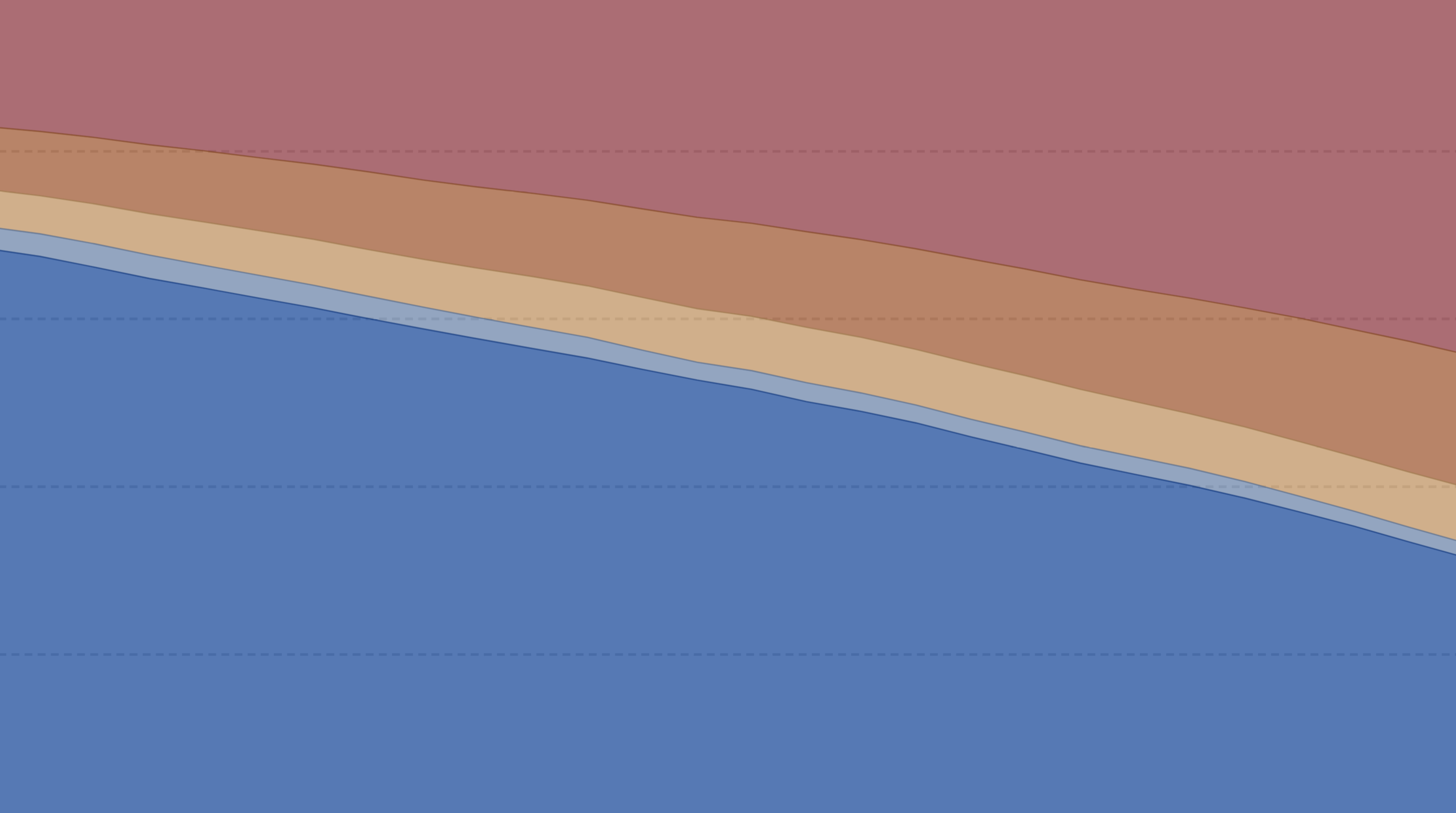

In the past, infectious diseases dominated. But death rates from infectious diseases have fallen quickly – faster than other causes. This has led to a shift in the leading causes of death. Now, non-communicable diseases – such as heart diseases and cancers – are the most common causes of death globally.

More progress is possible, and the impact of causes of death can fall further.

On this page, you will find global data and research on leading causes of death and how they can be prevented. This includes the number of people dying from each cause, their death rates, how they differ between age groups, and their trends over time.

This data can also help understand the burden of disease more broadly, and offer a lens to see the impacts of healthcare and medicine, habits and behaviours, environmental factors, health infrastructure, and more.

Research & Writing

Deaths from infectious diseases

How many people die from the flu?

Malaria: One of the leading causes of child deaths, but progress is possible and you can contribute to it

More than half a million children die from diarrhea each year. How do we prevent this?

Oral rehydration therapy: a low-tech solution that has saved millions of lives

Rotavirus vaccine – an effective tool that prevents children dying from diarrhea

Pneumonia — no child should die from a disease we can prevent

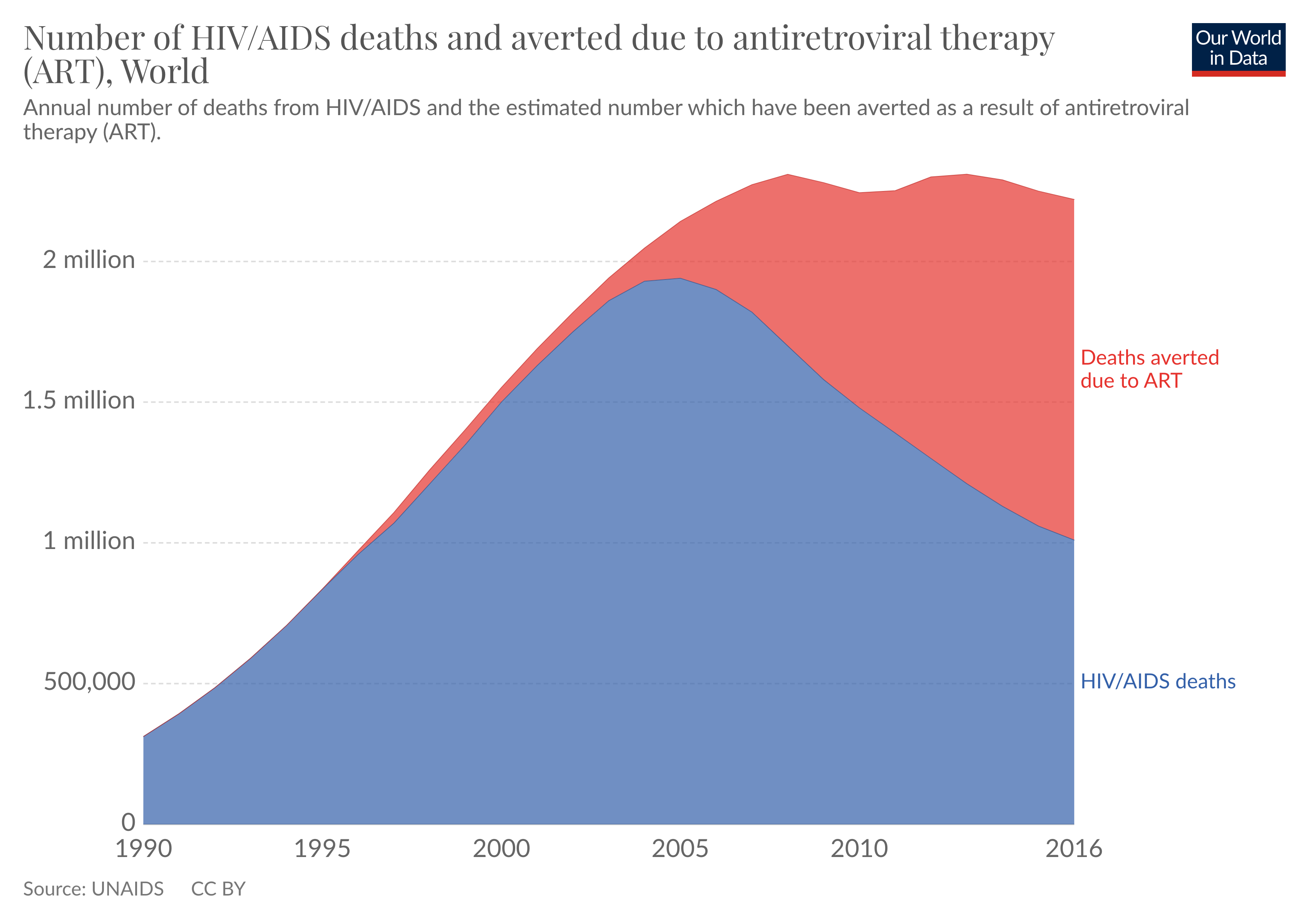

Antiretroviral therapy has saved millions of lives from AIDS and could save more

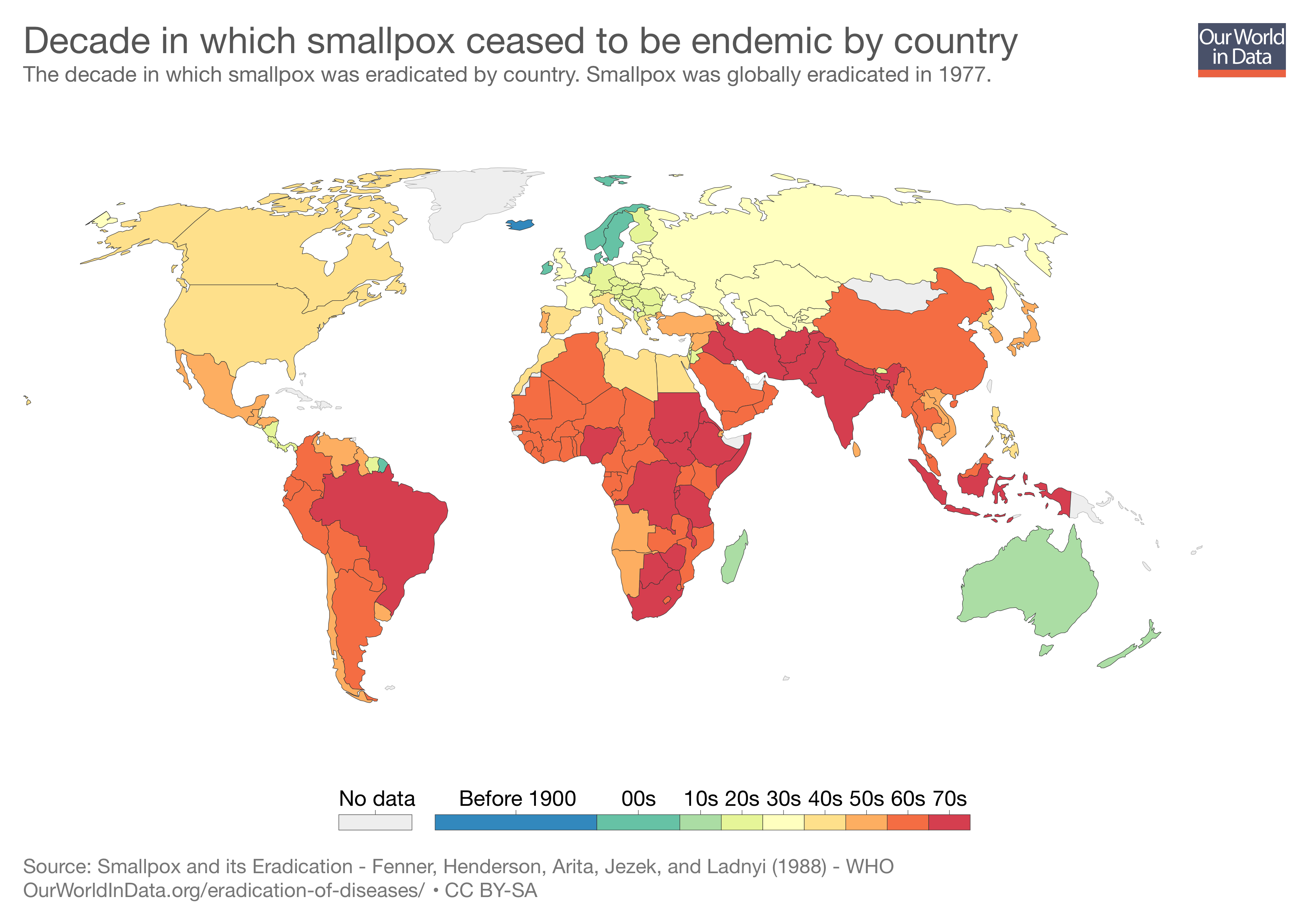

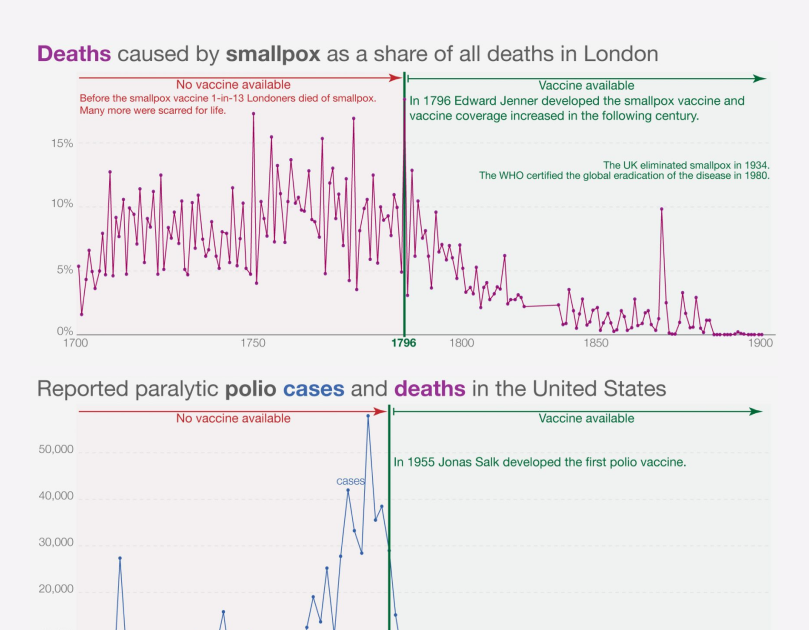

Smallpox is the only human disease to be eradicated - here's how the world achieved it

The Spanish flu: The global impact of the largest influenza pandemic in history

Our history is a battle against the microbes: we lost terribly before science, public health, and vaccines allowed us to protect ourselves

More articles on causes of death

Understanding data on causes of death

Endnotes

Although communicable and non-communicable diseases are shown separately, it is now understood that infectious diseases contribute to several non-communicable diseases.

This includes Helicobacter pylori and stomach cancer, human papillomavirus and cervical cancer, hepatitis C virus and liver cancer, Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis, Streptococcus pneumoniae and chronic respiratory diseases, and others.

In addition, infectious diseases can increase the risk of dying from non-communicable diseases. For example, several respiratory pathogens, such as the influenza virus, increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

Mercer, A. J. (2018). Updating the epidemiological transition model. Epidemiology and Infection, 146(6), 680–687. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268818000572

Behrouzi, B., Bhatt, D. L., Cannon, C. P., Vardeny, O., Lee, D. S., Solomon, S. D., & Udell, J. A. (2022). Association of Influenza Vaccination With Cardiovascular Risk: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 5(4), e228873. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.8873

This chart was inspired by related figures in the paper:

Schöley, J., & Willekens, F. (2017). Visualizing compositional data on the Lexis surface. Demographic Research, 36, 627–658. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.21

Out of these, death rates from falls have an especially strong age gradient.

Rockett, I. R. H., Regier, M. D., Kapusta, N. D., Coben, J. H., Miller, T. R., Hanzlick, R. L., Todd, K. H., Sattin, R. W., Kennedy, L. W., Kleinig, J., & Smith, G. S. (2012). Leading Causes of Unintentional and Intentional Injury Mortality: United States, 2000–2009. American Journal of Public Health, 102(11), e84–e92. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300960

Remund, A., Camarda, C. G., & Riffe, T. (2018). A Cause-of-Death Decomposition of Young Adult Excess Mortality. Demography, 55(3), 957–978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0680-9

Rockett, I. R., Regier, M. D., Kapusta, N. D., Coben, J. H., Miller, T. R., Hanzlick, R. L., Todd, K. H., Sattin, R. W., Kennedy, L. W., Kleinig, J., & others. (2012). Leading causes of unintentional and intentional injury mortality: United States, 2000–2009. American Journal of Public Health, 102(11), e84–e92.

Percentage of Deaths from External Causes,* by Age Group† - United States, 2017. (2019). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(32), 710. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a7

Armstrong, G. L. (1999). Trends in Infectious Disease Mortality in the United States During the 20th Century. JAMA, 281(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.1.61

Wise, D. A. (Ed.). (2004). Perspectives on the economics of aging. University of Chicago Press. Chapter 9. Cutler, D., & Meara, E. (2001). Changes in the Age Distribution of Mortality Over the 20th Century (No. w8556; p. w8556). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w8556

Drevenstedt, G. L., Crimmins, E. M., Vasunilashorn, S., & Finch, C. E. (2008). The rise and fall of excess male infant mortality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(13), 5016–5021. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0800221105

Jayachandran, S., Lleras-Muney, A., & Smith, K. V. (2010). Modern Medicine and the Twentieth Century Decline in Mortality: Evidence on the Impact of Sulfa Drugs. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2), 118–146. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.2.2.118

Mercer, A. J. (2018). Updating the epidemiological transition model. Epidemiology and Infection, 146(6), 680–687. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268818000572

Vaupel, J. W. (2010). Biodemography of human ageing. Nature, 464(7288), 536–542. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08984

Vaupel, J. W., & Yashin, A. I. (1985). Heterogeneity’s Ruses: Some Surprising Effects of Selection on Population Dynamics. The American Statistician, 39(3), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1985.10479424

Schöley, J., & Willekens, F. (2017). Visualizing compositional data on the Lexis surface. Demographic Research, 36, 627–658. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.21

For other risk factors, like obesity, they estimate the number of deaths that could be prevented if the risk factor was reduced to an ‘optimal level’, such as a BMI range.

Murray, C. J. L., Aravkin, A. Y., Zheng, P., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahpour, I., Abegaz, K. H., Abolhassani, H., Aboyans, V., Abreu, L. G., Abrigo, M. R. M., Abualhasan, A., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Abushouk, A. I., Adabi, M., … Lim, S. S. (2020). Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1223–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani, Fiona Spooner, Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2023) - “Causes of Death” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-causes-of-death,

author = {Saloni Dattani and Fiona Spooner and Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser},

title = {Causes of Death},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.