Gender Ratio

How does the number of men and women differ between countries? And why?

This article was first published in June 2019, and last revised in February 2024.

The ratio between the male and female population size is called the gender ratio. This ratio is not stable — it is shaped by biological, social, technological, cultural, and economic forces. In turn, the gender ratio has an impact on society, demography, and the economy.

On this page, we provide an overview of how the gender ratio varies across the world and over time. We present data on how it varies between age groups and the forces that influence the gender ratio.

Many argue persuasively that the terms "gender" and "sex" are not to be used interchangeably.1

In this context, we have made an exception — we speak of the "gender ratio" because it's a familiar term and will help people who want to search for the topic and learn about it. But we also speak of the "sex ratio" because it is more accurate in this situation – reflecting that the underlying data is based on sex — and because this term is increasingly used in the academic literature.

Related topics

Child and Infant Mortality

Child mortality remains one of the world’s largest problems and is a painful reminder of work yet to be done. With global data on where, when, and how child deaths occur, we can accelerate efforts to prevent them.

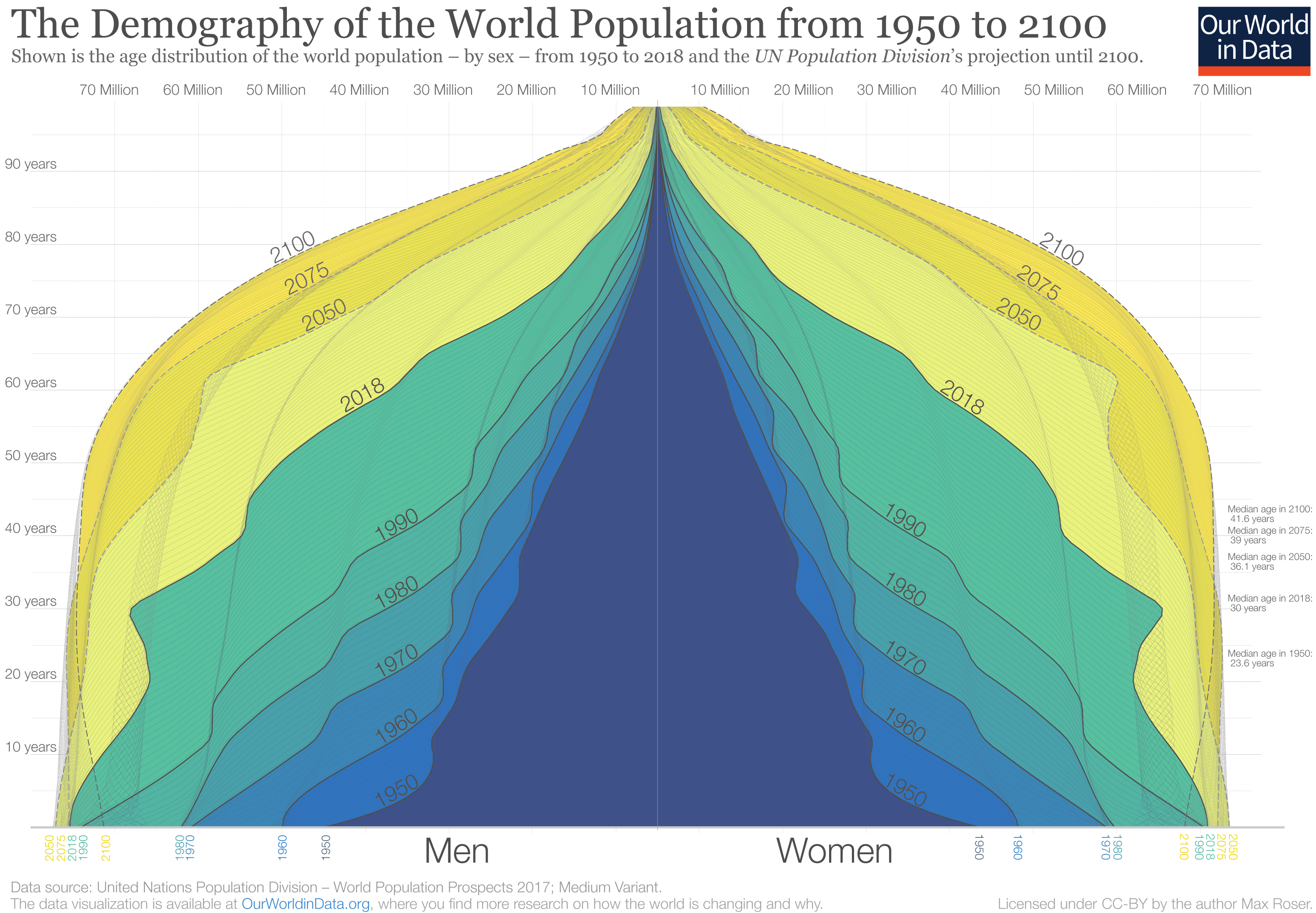

Age Structure

What is the age profile of populations around the world? How did it change and what will the age structure of populations look like in the future?

Other research and writing on the gender ratio on Our World in Data:

See all interactive charts on the gender ratio ↓

The gender ratio around the world

What share of the population is male and female?

Globally, in 2021, the female share of the global population was just under 50%.

But this share, and the sex ratio, vary around the world. There are three broad reasons for this:

- Births – the sex ratio at birth is not equal. In all countries, there are more male than female births, although the extent of this varies by country as we will see below. This means that all else being equal, we would expect the male share of the population to be higher.

- Deaths – there are sex differences in mortality rates and life expectancy. On average, women live longer than men. This means that all else being equal, we would expect the male share of the population to be lower.

- Migrations – immigration and emigration can vary by gender, which can be the effect of labor markets, conflicts, and other factors.

The balance of these factors determines the sex ratio of the total population.

In the map below, we see the sex ratio of populations: this is shown as the female share of the total population.

Countries over 50 percent (shown in orange) have a higher female population, while those below 50 percent (shown in purple) have a higher male population.

Most countries have a female share of the population between 49 and 51 percent (within one percentage point of an equal share of men and women).

There are however a few notable outliers:

- In several countries in South and East Asia — most notably India and China — there is a significantly lower female share of the population. These are countries where there are larger differences in the sex ratio at birth.

- In several countries in the Middle East, there is a higher male share of the population, such as Oman, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. By hovering over the countries you can see that the change over time. These tend to be countries with more male immigration.2

- In Eastern Europe, there is a higher female share of the population. Eastern European countries and Russia tend to have much larger sex gaps in life expectancy, from much higher mortality rates in adult men than women.

The sex ratio through the lifespan

In this chart we see the sex ratio — measured as the number of males per 100 females — at different ages through the lifespan.

As you can see, the sex ratios at birth and in childhood are higher than 100, meaning there are more boys than girls at these ages (“male bias”), in almost every country.

At ages 15 and 20, the sex ratio is still higher than 100. Among adolescents and young adults, the ratio at a global level is affected by the male bias in birth ratios and the impact of the most populated countries, such as China and India, which have very skewed sex ratios.

But as we move through adulthood, the sex ratio declines. In 2021, among 50-year-olds the ratio was close to 100. Among 70-year-olds, there were only 86 men per 100 women. In the very oldest age bracket, people aged 100 and older, there were only 24 men per 100 women.

You can explore this data for any country or region of the world using the "Change country" button in the chart.

For some countries, you can see that the decline in the sex ratio with age is even more extreme — in Russia, for example, by age 50 there were only 91 males per 100 females in 2021. By 70 years old, there were around half as many men as women.

In every country in the world, women tend to live longer than men. Whilst this is true today, it hasn't always been the case.

In our article "Why do women live longer than men?", we take a look at the data and explanations for why this is the case.

Why do women live longer than men?

Women tend to live longer than men around the world – but the sex gap in life expectancy is not a constant.

The sex ratio at birth

Across the world, there are differences in the sex ratio at different life stages.

In some cases, this imbalance traces back to birth: in some countries, the sex ratio of babies born each year is heavily skewed.

In the map below, we see the sex ratio at birth across the world.

Here the sex ratio is measured as the number of boys born for every 100 girls. A value greater than 100 means there are more boys born that year. A value of 110 would indicate that there are 110 male births for every 100 female births.

The first striking point is that, in every country, there are more boys born than girls.

This has been true across all years for which we have data, in each country, as you can see if you press the "Play timelapse" button.

Is this because there is selection for baby boys before birth – for example, through sex-selective abortion practices? Not necessarily.

Even without sex-selective abortion, births in a given population are typically male-biased — the chances of having a baby boy are slightly higher than having a girl.

Why are births naturally expected to be male-biased?

In most countries, there are around 105 males per 100 female births.

This is what the World Health Organization (WHO) considers the "expected sex ratio at birth”, which means that, in the absence of gender discrimination or interference, it’s expected that there would be around 105 boys born per 100 girls — although this can range from around 103 to 107 boys per 100 girls.

But why is this ratio expected? Why are babies more likely to be boys?

In a comprehensive study, Orzack et al. (2015) analyzed the sex ratio of babies throughout the stages of pregnancy – from conception through to birth – using five different methods.3

This produced a large dataset on the sex ratio.

A key result from this study was that the sex ratio at conception is equal: there is no difference in the number of males and females conceived.

So, the male-biased sex ratio at birth must be because of other differences during pregnancy — in the probability of miscarriage through pregnancy.

The study found that, overall, the risks of miscarriage are higher for female fetuses than males.

But this varied between different stages of pregnancy:

- There is a higher probability that a zygote with chromosomal abnormalities4 is male. Therefore, in the first week of pregnancy, there is a higher risk of male mortality.

- In the next 10–15 weeks of pregnancy, there is a higher risk of female mortality.

- Around week 20, male and female mortality is approximately the same.

- Between weeks 28-35 of pregnancy, there is a higher risk of male mortality.

Overall, this results in a male-biased sex ratio at birth.

In some countries, the sex ratio is skewed beyond the expected sex ratio

Some degree of male bias in births is expected even without deliberate sex selection by parents or society.

But there are some key outliers in the world — such as China, India, Vietnam, Pakistan, and Azerbaijan – where this ratio is very skewed. Here, it's likely that deliberate selection practices are part of the reason why, as we explore below.

The sex ratio varies with birth order

Most countries have a sex ratio at birth around the expected range of 105 boys born for every 100 girls.

But in some countries, this ratio is higher, because of a preference for a son. This preference is even more visible if we break down the data by the “birth order” of children, i.e. by their order of birth.

The chart shows data from India, and how sex ratios vary if you look at the first child in a family or the second, third, fourth, or fifth-born child.

The data is adapted from the Economic Survey 20185 and based on data from the DHS and National Family Health Surveys in India.

As you can see, the sex ratio is shown for two different categories:

- On the left, the sex ratio among children who are not the last child born in their family (i.e. their parents have more children afterward)

- On the right, the sex ratio among children who are the last child born in their family (i.e. their parents stop having children afterward)

Let's first focus on the top row, which presents the data for India as a whole.

On the left, we see the sex ratio at birth among children who are not the last child in their family. Among first-born children, the sex ratio is very close to what we would expect "naturally": a ratio of around 105 boys per 100 girls.

But for the second, third, fourth, and fifth-born children, this ratio is skewed towards girls. In other words, when a girl is born, parents are more likely to have another child. This is evidence that parents tend to continue to have children until they get a son.

On the right, we see the sex ratio when the child is the last — these ratios are much more skewed towards boys. This is consistent across the birth order: whether it's the second, third, fourth, or fifth child, a family is much more likely to stop having children when they have a boy.

Overall, we see a strong preference for a son in India — parents are more likely to continue having more children when their child is a girl, and they are more likely to stop having children when they have a boy.

Let’s look at the second row, which shows sex ratios in Indonesia. Sex ratios here do not diverge strongly from the expected ratio of 105, and there is no clear difference when the child is or isn't the last to be born. This indicates that parental choices on when to have more children don’t point to a strong preference for a son or a daughter.

In the third row, we see that within India there are large differences in son preference across different states. The data shows that there are states with "weaker" and "stronger" preference for a son.

Sex selection practices also became more prominent for later births

From the research above, we see that the sex of a child can be, in some countries, a factor parents use to decide whether to stop having more children.

But the birth order also influences the use of prenatal sex selection, i.e. sex-selective abortion. We see evidence of this across several countries.

Using Indian national survey data from 1976 to 2005, researchers looked at how the sex of children and birth order affect the use of prenatal selection.6 They found a significant and increasing skew in the sex ratio since the 1980s — a time when the average woman in India had four children.

When the firstborn or the first- and second-born child was a girl, then the second or third child was more likely to be a boy. This skewed ratio can only be explained by prenatal sex selection in favor of boys.

Another study of a large Delhi hospital known for maternal care showed very similar results.7 The overall sex ratio was male-biased with only 806 girls per 1,000 boys. But this got significantly worse when the family already had a daughter: there were 720 girls per 1,000 boys in families with one previous girl, and only 178 girls per 1,000 boys in families with two previous daughters.

Even among women who hadn’t practiced sex-selection abortion, mothers with a girl were more likely to report taking ineffective alternative medicines for sex-selection purposes.

This finding is, of course, not restricted to India. Many countries across Asia in particular show similar patterns.

In this chart, we can see how the sex ratio in South Korea varies by birth order.

There was a very steep rise in the sex ratio of third-, fourth- and later children through the 1980s. By the early 1990s, there were more than 200 boys per 100 girls for third-born children. For fourth-born children or higher, the ratio was close to 250:100.

This occurred at a time when the number of children per woman was falling quickly: in 1970, the fertility rate was more than four children per woman, and by the 1990s this had fallen below two.

You can also view the data for China, by using the "Change country" button in the chart.

Sex ratios in China have also been clearly affected by birth order.8 Here we see that since 1980 — a period in the middle of a rapid reduction in period fertility rate — there has been a rise in the bias for male first-born children: rising from the expected 105 boys to 114 boys per 100 girls.

But we see a much more significant skew in the ratio in second or third-born children. For third-born children, the ratio was 158 boys per 100 girls.

South Korea provides an important example where the male bias can be successfully addressed. But for several countries across Asia, the data shows that many parents still strongly prefer a son.

The sex ratio in childhood

Sex ratios — the ratio of males and females — at birth are male-biased across every country in the world. In our section above, we explain why we'd expect this to be the case for biological reasons. The so-called "expected" sex ratio at birth was around 105 males per 100 females.

But how does this ratio look later in childhood? Does it vary between newborns and five-years-olds?

The map below shows the sex ratio among five-year-olds across the world. Just as with the sex ratio at birth, we see the highest ratios in several Asian countries, where the share of boys is higher than we would expect.

In China, there were close to 115 boys per 100 girls at age five, in 2021. In India, there were around 109 boys per 100 girls.

In the chart below, we see a scatterplot comparison of the sex ratio at birth (on the y-axis) versus the ratio at five years old (on the x-axis).

The grey line here represents parity: where countries have the same sex ratio among five-year-olds as the ratio among newborns. As we see, many countries are found slightly above this line, which means the sex ratio for newborns is higher than for 5-year-olds.

In these countries, male bias tends to weaken through the first years of childhood. Why is this the case?

As we explore in the next section, infant and child mortality rates are higher for boys than for girls across countries. Fewer boys survive the first few years of life. For most countries, this results in a decline in the sex ratio.

Overall we see that, despite a higher child mortality in boys, the sex ratio at age five in the majority of countries is still over 100: meaning that boys still outnumber girls in childhood.

Why do boys die more often than girls?

Child and infant mortality is higher for boys in nearly all countries

Child mortality measures the share of newborns who die before reaching their fifth birthday. In the chart below, we see a comparison between child mortality in boys and girls.

The mortality rate among boys is shown on the y-axis and the mortality rate among girls on the x-axis. The grey diagonal line shows where the mortality rate among both sexes is equal. In countries that lie above the line, the mortality rate among boys.

What's striking is that child mortality is more common for boys in all countries of the world, with the exception of India. We explore why India is an outlier in the section below.

Child mortality has been falling rapidly across the world, especially over the past century. This has been true in boys and girls alike.

It has been known for a long time that the mortality of boys is higher. As early as 1786, the physician Dr. Joseph Clarke read a paper to the Royal Society of London on his observations that "mortality of males exceeds that of females in almost all stages of life, and particularly the earliest stages".9

What do infants die from?

Why is it the case that boys die more often than girls? First of all, it's important to understand what young children die from.

In this chart, we see death rates in infants across different causes, globally. This data comes from the IHME's Global Burden of Disease study, which provides estimates by sex. The y-axis shows death rates in boys, and the x-axis shows death rates girls.

Causes of death above the grey line are more common in boys.

The chart shows that for many major causes of death, mortality is higher in boys.

There are some causes — HIV/AIDS, nutritional deficiencies, whooping cough, among others — for which the mortality rates are higher in girls. But overall, infant boys are more likely to die in childhood than girls.10

Boys are more vulnerable in two key ways: they are at higher risk of birth complications, and infectious disease. We explore the possible reasons for this below.

Boys are at higher risk of birth complications

The higher death rates seen in boys are visible in the first few days of life – they are more likely to die from preterm births, asphyxia, birth defects, and heart anomalies, compared to girls. But why?

First of all, boys are more likely to be born prematurely: the share of boys born before full-term pregnancy is higher than for girls.11

This occurs naturally but is exacerbated by the rate of induced preterm births. Boys tend to have a higher birthweight than girls — which can increase the risks to mothers and the baby if they wait to deliver — so boys are more likely to be induced before the end of the pregnancy term.12 One reason that more boys die from preterm births is that preterm births are more common among boys.

Boys also have higher death rates in the first week of life.13

Although boys are on average heavier than girls at birth, their organs tend to be less physically mature at birth. They tend to have delays in their development of physiological functions, such as lung function and the function of other organs.14 For example, poorer lung function in newborn boys has been shown for both term and preterm infants.15

The reason for these differences has been an important question for decades — although the answer is still not clear and may be complex.

But there are several hypotheses. One is that the production of surfactants in the lung has been observed earlier in female fetuses, leading to improved airway flow in the lungs. Another is that estrogen may contribute to earlier lung development in female fetuses. Another is that males on average have a higher birthweight, meaning they may trade-off increased size for functional development. Another hypothesis is that the uterus may be less hospitable to male fetuses — because they have a Y chromosome, this may lead the mother’s immune system to react to their central nervous system.16

These explanations — combined with a higher risk of premature birth — may explain why boys have higher rates of asphyxia, respiratory infections, and birth defects.

Boys are at higher risk of infectious diseases

Boys are also at higher risk of several infectious diseases. This is more generally true for a broad range of infections, spanning person-to-person, vector-borne, blood-borne, and food and water-borne diseases.17

We see this clearly when we compare mortality rates for boys and girls in the earlier chart. But why are boys more susceptible to infection?

Overall, boys have a less developed immune system. There are related hypotheses for why.

The Y chromosome in boys increases their vulnerability. While females have two X chromosomes (XX), males have one X and one Y chromosome (XY). The X chromosome contains a larger number of immune-related genes, and having two X chromosomes may mean that newborn girls have a stronger immune system.18 This makes males more vulnerable to many infectious diseases.

But the stronger immune response of females comes with a cost. It’s the reason why women are more susceptible to autoimmune disorders, such as Hashimoto's disease and Addison’s disease.19

Males are also more susceptible to a range of genetic disorders due to their single X chromosome. Mutations on the X chromosome tend to have more severe impacts in males, as they do not have a second X chromosome that can compensate. This makes them particularly vulnerable to conditions associated with abnormalities on the X or Y chromosomes.20

Sex hormones may be another reason for weaker immune systems in males. Males have much higher levels of testosterone, which seem to inhibit B and T-cells of the immune system. Estrogen, on the other hand, tends to enhance immune function. Overall, male hormones suppress the immune system relative to females.21

The male disadvantage

The fact that boys are more susceptible than girls to a range of health conditions is often summarized as the “male disadvantage”. This is not restricted to childhood — the female survival advantage carries into adulthood. It’s part of the reason why women tend to live longer than men.

The leading explanations for the "male disadvantage" are based on biological sex differences. More specifically, differences in the physiological maturity of organs, sex chromosomes, and hormones.

In circumstances where both sexes are treated equally, we would therefore expect infant and child mortality rates to be slightly higher for boys.

Missing girls and women

Biology or discrimination: which countries have skewed sex ratios at birth?

Today, and at several points historically, the sex ratio at birth in some countries is too skewed to be explained by biological differences alone. The "expected sex ratio at birth" is around 105 males per 100 females.

In a recent study, Chao et. al (2019) re-modelled sex ratios at birth (SRB) across the world based on a range of population sources, including census and household survey data.22

The authors identified 12 countries with strong statistical evidence of a skewed sex ratio: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, China, Georgia, Hong Kong, India, Montenegro, South Korea, Taiwan, Tunisia, and Vietnam. The results are shown in the chart below since 1950. 23

Most of these countries are in Asia. Why is this the case? Is there a biological or environmental difference, or is it the result of discrimination?

Hepatitis B was proposed as an explanation then later debunked

Amartya Sen was one of the first scholars to bring public attention to the concept of "missing women" as a result of sex-selective abortion, unequal treatment, and infanticide of girls.24

The reason for this skew in sex ratio has been previously challenged. One hypothesis was put forward by economist Emily Oster. In a 2005 paper, she argued that a large proportion — approximately 45%, around 75% in China, 20–50% in Egypt and western Asia, and under 20% in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal — of the overrepresentation of men could be explained by the high rates of hepatitis B carriers in Asia.25

The rationale was that people infected with hepatitis B appeared to have an offspring sex ratio much more in favor of boys (1.5 boys per girl), and that hepatitis B infection rates were notably higher in Asian cultures than in the West. The combination of these two observations, Oster estimated, could account for a large proportion of the "missing women".

A few years later, Oster refuted her own hypothesis on the role of hepatitis B in a paper titled "Hepatitis B does not explain male-biased sex ratios in China". In a study of 67,000 people in China — 15% of which were infected by hepatitis B — Oster and colleagues found no link between hepatitis B status and offspring sex ratio.26 People infected by hepatitis B, regardless of whether they were mothers or fathers, were not more likely to have a boy than people without hepatitis B. The authors concluded that hepatitis B rates could not explain the skewed sex ratio in China.

Other studies — such as that by Lin and Luoh (2008) in Taiwan — have also found minimal to no effect of hepatitis B on the sex ratio.27

Sex-selective abortions and discrimination against girls

After the hepatitis B hypothesis was debunked, no clear evidence of a biological reason for such skewed sex ratios emerged.

There is some variability in the "expected sex ratio”, which may result from biological or environmental factors — a figure of 105 boys per 100 girls is usually considered the expected range, but this can vary from 103 to 107 boys per 100 girls. Regardless, the natural variability in the sex ratio is too small to explain the high ratios in some countries.

There is now strong evidence for sex-selective abortion and discrimination against girls across several countries. Not only does the rise in sex ratios coincide with the availability of technology to determine prenatal sex, there is also clear evidence from research investigating the use and promotion of such technologies.

In India, for example, prenatal diagnosis became available in the 1970s, shortly after medical abortion was legalized in 1971.28 Whilst the use of prenatal diagnosis was intended to detect abnormalities, it was soon used and promoted by the Indian medical profession to determine the fetus’s sex.29 Even after this use was prohibited, studies suggest many gynecologists did not believe sex-selection abortion was unethical and argued that it was an important intervention to balance population control with the desire for sons.30

Results from some of the earliest studies on abortions, following the availability of prenatal sex determination, are striking. Between 1976 and 1977, at an urban hospital in India, 96% of the girls who were tested were aborted. In contrast, all of the 250 boys tested, including those with an identified risk of genetic defect, were born.31 At a clinic in Mumbai, all of the 15,914 abortions after sex determination in 1984–1985 were girls. Results from another six hospitals in the city found that 7,999 of the 8,000 aborted fetuses in 1988 were girls.32

The evidence that highly skewed sex ratios at birth have been largely the result of gender discrimination and selective abortions has been well-established across several countries. We discuss the reasons for this discrimination in a later section on this page.

There are some additional hypotheses as to why the sex ratio at birth is skewed in some countries.

Based on Chinese census data, Shi and Kennedy (2016) argue that the skew in China's sex ratio is not the result of selective abortion practices, but much more the result of administrative anomalies.33 The authors argue that the one-child policy led some parents to postpone the registration of daughters (making them appear "missing"), but that they appear later in Chinese census data. A year later, Cai (2017) challenged the authors" conclusions in support of the conventional hypothesis that this is not a statistical artifact, but a real demographic and social challenge.34

Infanticide

Sex discrimination can occur prenatally, in the form of sex-selective abortions, as we discuss here, or postnatally, when in the very worst cases, it can lead to the death of a child.

The death of a child due to sex discrimination can be due to the deliberate killing of an infant (“infanticide”) or by neglect, poor and unequal treatment.

Prenatal discrimination increased as both abortions and sex determination technologies became more readily available. However, postnatal discrimination also occurs and has a long history.

Infanticide has a long history

Infanticide (also called infant homicide) — the deliberate killing of newborns and infants — has a long history.35

From hunter-gatherers to ancient civilizations to the present day: infanticide has spanned all periods of history. Anthropologist Laila Williamson goes as far to say: “Infanticide has been practiced on every continent and by people on every level of cultural complexity, from hunter-gatherers to high civilizations, including our own ancestors. Rather than being an exception, then, it has been the rule."36

Humans are not alone. From birds to rodents, fish, and mammals, we find evidence of infanticide across the animal kingdom.37

There are some common misconceptions today surrounding the practice of infanticide. Although the term is now often adopted as a synonym for "female infanticide" — the killing of unwanted girls — the gender specifics and drivers of infanticide depend on context and time in history.38

Historical evidence and estimates of infanticide

Many researchers have studied the demographic, health, and cultural profiles of prehistoric societies. In rare cases, they can use indirect evidence of the fossil record, but many rely on modern hunter-gatherer societies today.39

Estimates for infanticide in prehistoric societies are very high. Using recent hunter-gatherer societies as a proxy, some studies suggest anywhere from 15% to 50% of newborns were killed in the first year of life.40 Other estimates are lower, but still very high: in the range of 15–20%.36

Hill & Walker (2007) looked at the demographic profiles, death rates, and causes of death of recent hunter-gatherers: the Hiwi group of Venezuela. They did this using census and interviews gathered over seven years.41 They found very high rates of infant death from violence. Infant mortality rates in the past were very high — most studies suggest around a quarter of newborns did not survive the first year of life. In the Hiwi hunter-gatherers, researchers found homicide to be the second largest cause of death, accounting for 30%. They also found large sex differences: infanticide rates were four times higher among girls than boys.

Other studies of have analyzed the sex ratio of infants in modern hunter-gatherer societies to estimate the prevalence of infanticide. A very skewed sex ratio of infants is suggestive of select infanticide. In studying 86 hunter-gatherer bands across North America, South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia, researchers found high levels of female infanticide across 77 of them.42

This is shown in the table, where there were many more young males than females in bands where infanticide was reported as "common" or "occasional".

Infanticide reported as: | Youth sex ratio (males per 100 females) | Adult sex ratio (males per 100 females) | Number of hunter-gathering bands |

|---|---|---|---|

Common | 138 | 105 | 71 |

Occasional | 138 | 80 | 6 |

Not common | 100 | 85 | 3 |

Not practised | 94 | 83 | 6 |

The practice of infanticide was not just common in prehistoric societies, but was also very common in many — but not all — ancient cultures.43 Evidence for this exists either in the form of preserved burial remains, documented records, or writings suggestive of the practice.44

Both sexes are victims of infanticide

It’s a common assumption that infanticide relates only to female infanticide: the killing of unwanted girls.38 But the role or direction of gender discrimination — either towards boys or girls — varies between contexts.45

Sometimes there is no clear gender discrimination, and it occurs for both sexes.

There is of course significant evidence of female-selective infanticide throughout history: we see that in the sex ratios of many hunter-gatherer societies described above through to skewed ratios in Medieval England.46 Evidence of male-selective infanticide is rarer, but does exist: in a sample of 93 preindustrial cultures, 9 showed evidence of female-selective, while 1 showed male-selective infanticide.45

Even today, cases of infanticide still exist, despite being outlawed in most countries.47 Infanticide occurs in Western countries: in some (such as the United States) boys make up a higher share of infant homicides.48

But the most widely prevalent — and selection that has a significant impact on gender ratio — is female infanticide. This remains reported across countries with a strong son preference: India and China are the most documented examples.49

Infanticide is the most direct case of postnatal sex selection. More often overlooked is the “excess mortality” that results from neglect and unequal treatment of girls. This phenomenon is often referred to as “delayed infanticide”.

Excess female mortality

Poor treatment of girls results in increased mortality in childhood

In almost every country, young boys are more likely to die in childhood than girls — as we explore above, there are several biological reasons for this. But this is not true in a few countries — India is a notable example where girls die more often than boys.

When we compare mortality rates of infants (under one year old) and children under five between boys and girls in India, we see that the difference is greater among children under five. While infant mortality rates are approximately the same, the child mortality rate for girls is higher.

Let's then focus on children rather than infants.

In the chart, we see mortality rates for boys (on the y-axis) and girls (on the x-axis) for various causes in India. This data is shown for children aged 1-4 years old.

Here we see that death rates are significantly higher for girls for many causes of death. Some of these — hepatitis, measles, or tuberculosis, for example — we expect to be higher in girls. But not infections, respiratory diseases, and diarrheal diseases.

Note also that there are much higher mortality rates for nutritional deficiencies and protein-energy malnutrition among girls.

Poorer health outcomes in girls in some countries — often across Asia and not restricted to India — has been well-documented.50 Even in some countries, where the child mortality rate remains higher in boys than girls, death rates for girls are still higher than would be expected.

Social preference for a boy has resulted in the unequal treatment of young girls in a number of ways. Studies have shown in some countries:

- Poorer nutrition for girls and unequal food distribution;51

- Less breastfeeding from mothers for daughters than for sons;52

- Lower healthcare utilization for girls;53

- Preferential treatment for boys during pregnancy, with more antenatal visits and higher rates of tetanus vaccination.54

This combination of poorer nutrition and healthcare investment can result in higher mortality rates for girls, but also excess mortality in women at later stages of life.

How many women are missing?

The term “missing women” was first coined in 1990 by Indian economist Amartya Sen, who estimated that "more than 100 million women are missing".55

"Missing women" describes the gap between the actual number of women in a population and the expected number of women in a population if sex discrimination was absent. In other words, the number of additional women who would be alive if sex discrimination was absent. It includes women missing due to practices like sex-selective abortions, as well as those who die prematurely due to infanticide, neglect, or maltreatment later in life.

Many researchers have tried to estimate the number of missing women. Using sex ratios at birth and other ages, they compare the observed and expected values: the difference is then defined as the number of girls and women who are missing.

There are several challenges in calculating this figure.

For the observed sex ratio, one concern is the accuracy of the reported number of births, and the number of men and women in the population.

Another major issue is knowing exactly what the expected sex ratio would be at each stage in life. For example, the “expected sex ratio at birth” is said to be 105 male births per 100 female births. But through time and across the world, this can often vary, between 103 to 107 male births per 100 female births.

The combination of these measurement issues means that any estimate of the number of missing women comes with fairly high uncertainty.

In the table here we provide a summary of a range of estimates — note here that the year of the estimate is different for each. We can see that, although there is significant uncertainty, all estimates are within the range of over 50 million by 1990, and likely upwards of 100 million today.

In the chart, we see some of the most recent estimates of missing women from 1970 through to 2015 from Bongaarts & Guilmoto (2015).56 The researchers estimated there were 61 million missing women in 1970, and by 2015 there were 136 million. This is more than the population of Mexico in 2021.

Source | Number of missing women | Year the estimate is for |

|---|---|---|

Sen (1990, 1992) | More than 100 million | 1990 |

Coale (1991) | 60 million | 1990 |

Klasen (1994) | 92 million | 1990 |

Klasen and Wink (2002) | 102 million | 1990s |

Hudson & Den Boer (2004) | 90 million | 2000s |

Guilmoto (2012) | 117 million | 2010 |

Bongaarts & Guilmoto (2015) | 136 million | 2015 |

The authors also provided projections of the number of missing women through demographic changes to 2050, shown below.

We see that more than the majority of missing women would be from China and India.

How many girls and women are missing every year?

Above are estimates of the total number of missing women in the world. But how many are "missing" each year?

In this chart, we see estimates of the number of “missing” female births from prenatal sex discrimination, and excess female deaths as a result of postnatal discrimination.57

Until 1980, nearly all missing women were the result of excess female mortality. But sex-selective abortions — shown as “missing births” – became more common from the 1970s onwards.

For 2015, the authors estimated that a total of over 3 million women were missing in 2015 — around half from missing births, and the other half from excess female mortality.

Why is there a preference for a son in some places?

In countries where there is a clear imbalance in the sex ratio, there's a preference for a boy. But why does this preference exist?

Son preference is most common in countries across East and South Asia, but also in some countries in the Middle East and North Africa.58 Although there are significant cultural, economic, and societal differences between these countries, there are important parallels that explain strong preferences for a boy.

What these countries tend to have in common is a strong logic of “patrilineality”: the logic that productive assets move through the male line within the family.59

Although many other countries also have patrilineality to some degree, researchers find this logic is much more rigid in countries with a strong preference for a son. The social order of families resides with the male — lineage is passed from father to son. Men within the social order are the fixed points, and women the moving points: when a daughter marries, she leaves the current family to join a new one.

This can produce economic and social benefits to having a son rather than a daughter, including:

- Family name: the lineage within a family stays within the male line. Having a son therefore continues the family name.

- Old age support: sons within a family are often responsible for supporting parents in illness and old age.58 Elderly parents often live with married children and overwhelmingly so with their sons. This provides a strong economic incentive for a son for old age support. It's a key differentiating factor between countries with and without strong son preference: in Taiwan, it's rare for parents to live with a married daughter, but in the Philippines (without strong son preference) parents are equally likely to live with the son or daughter.59

- Dowries: a dowry — the transfer of property or money from the bride's to the groom's family — is an important economic concern for having a daughter. Studies in India have suggested that a dowry is the most common reason for not wanting a girl.60 Even when parents themselves didn't have a dowry in their own marriage, many expect they have to provide one for their daughter, or ask for one from a future daughter-in-law.

- Labor force opportunities: sons can bring better economic opportunities for a family. This can be the result of sex differences in economic opportunities, but also results from undervaluing the work of women. In many countries, unpaid or informal work accounts for a majority share of female employment. In this sense, informal employment is often seen simply as an extension of a woman's domestic work rather than being valued in its own right.59

- Family and societal pressure: it's not just economic concerns that parents worry about — surveys also reveal persistent pressures from family members and communities. In interviews, women often note pressures from female in-laws and husbands, and verbal and physical abuse when they didn't produce a son or were pregnant with a girl.61

- Religion: in some cultures, it's believed that only a son can light the funeral pyre and carry out death-related rites and rituals needed for salvation.62

What are the consequences of a skewed sex ratio?

Across several countries in Asia and North Africa, we see highly skewed sex ratios in favor of males. Strong preference for sons has led to an increasing number of "missing women" and therefore an "excess of males".

There are several adverse consequences of highly imbalanced numbers of men and women in society. These present a risk to men, women, family structures, and society as a whole.

The obvious consequence of gender imbalance is a large number of unmarriageable men.63 This could have several impacts on marriage dynamics for men:64

- Many men will have to delay marriage

- This could have a knock-on impact on younger men: not only will they be impacted by a skewed sex ratio for their generation, but will also have a "backlog" of men from the previous generation in the "marriage market'

- A significant number of men will have to forego marriage altogether

- The poorest men will likely be most highly impacted by this — it's hypothesized that women will "marry up" in society, leaving the men with the least resources disproportionately affected

- One of the most common reasons for son preference is for family lineage (the passing down of the family name through males in the family), which will likely not occur in families where sons do not marry

Whilst we might assume that this dynamic would favor women, they could also suffer negative consequences:

- A women's value may be increasingly lie in her role as a wife, daughter-in-law, or mother. This may deny her alternative pathways, such as remaining single or becoming more career-oriented

- Women may feel increased pressure or incentives to marry or have children earlier in life (possibly closing off different economic or labor opportunities)

- Women may be at increased risk of violence (emotional, sexual or physical) or trafficking65

Imbalanced gender ratios could negatively affect both men and women.

For society more broadly, there are several hypotheses that it will also result in more crime, violence, and disorder in communities. The rationale is that not only will there be an excess of men who don’t marry and have their own families, but also that the most affected will be those of the lowest socioeconomic status, the most uneducated, and with fewer opportunities.

Hudson and Den Boer proposed in 2005 that this situation could result in significant social stability and security concerns.65 Although studies have found a correlation between the prevalence of violence and more imbalanced gender ratios, it's difficult to disentangle a causal effect.66 Other researchers suggest that the evidence doesn’t support this concern: that rather than showing through aggression and violence, excluded men will be more marginalised, lonely, and at risk of psychological problems.63

What's clear is that the persistence of imbalanced sex ratios means there will be demographic consequences for many decades to come.

What affects the strength of gender bias?

Are richer and more educated parents less likely to have gender preference?

If our aim is to address the issue of a skewed sex ratio and female discrimination, an obvious question to ask is: will development fix the problem?

Is it the case that son preference is restricted to those at lower incomes, and therefore the problem would disappear if poverty fell and societies developed?

The evidence to date suggests the answer is no — development on its own does not address it.

Studies that have looked at the extent of sex ratio imbalances in different demographics — comparing income level, education, literacy, and employment factors amongst others — often conclude the opposite: that richer, urban families tend to discriminate more than the poor.67

For example, in North India, higher castes (who tend to be richer) had more skewed sex ratios than lower castes.68 Narrowing in on specific districts and households in India and South Korea suggested that richer families show greater discrimination.59

Despite rising incomes and development across many countries in Asia, North Africa, and Eastern Europe, the sex ratio got worse, not better.

Why is this? The link between rising incomes with development and an increase in the sex ratio may be fertility rates.

As we show on our page on fertility rates, rising development has a strong impact on reducing fertility. And falling fertility rates in turn exacerbate gender preference. This is often called the “fertility squeeze”.

In smaller families, you're less likely to have a son by chance

Imagine you have five or six children: there's a very high chance that at least one of them will be a boy. For five children, there's around a 98% chance you'll have a son.69

Now imagine you have only one or two children: the likelihood you have a son is much smaller. If you have only one child, you're chances of having a son are just over half (52%); if you have two children, the odds are 77%.70

In many countries across the world, this transition has happened. In India, average fertility rates fell from almost 6 children per woman before the 1960s to 2 in the 2010s; in China, it also fell from over 6 in the mid-20th century to below 2 since the 1990s. In South Korea, it fell from over 6 in the 1950s to just one child per woman since the 2000s.

As countries have become richer, education levels have increased; women have gained more rights to education, labor participation, and healthcare decisions, and fertility rates have fallen rapidly.

But the result is that if parents really want a son, their chances of having one naturally are now much lower. For parents of fewer children with a strong son preference, sex-selective abortion therefore became a much more important option.

Evidence from India

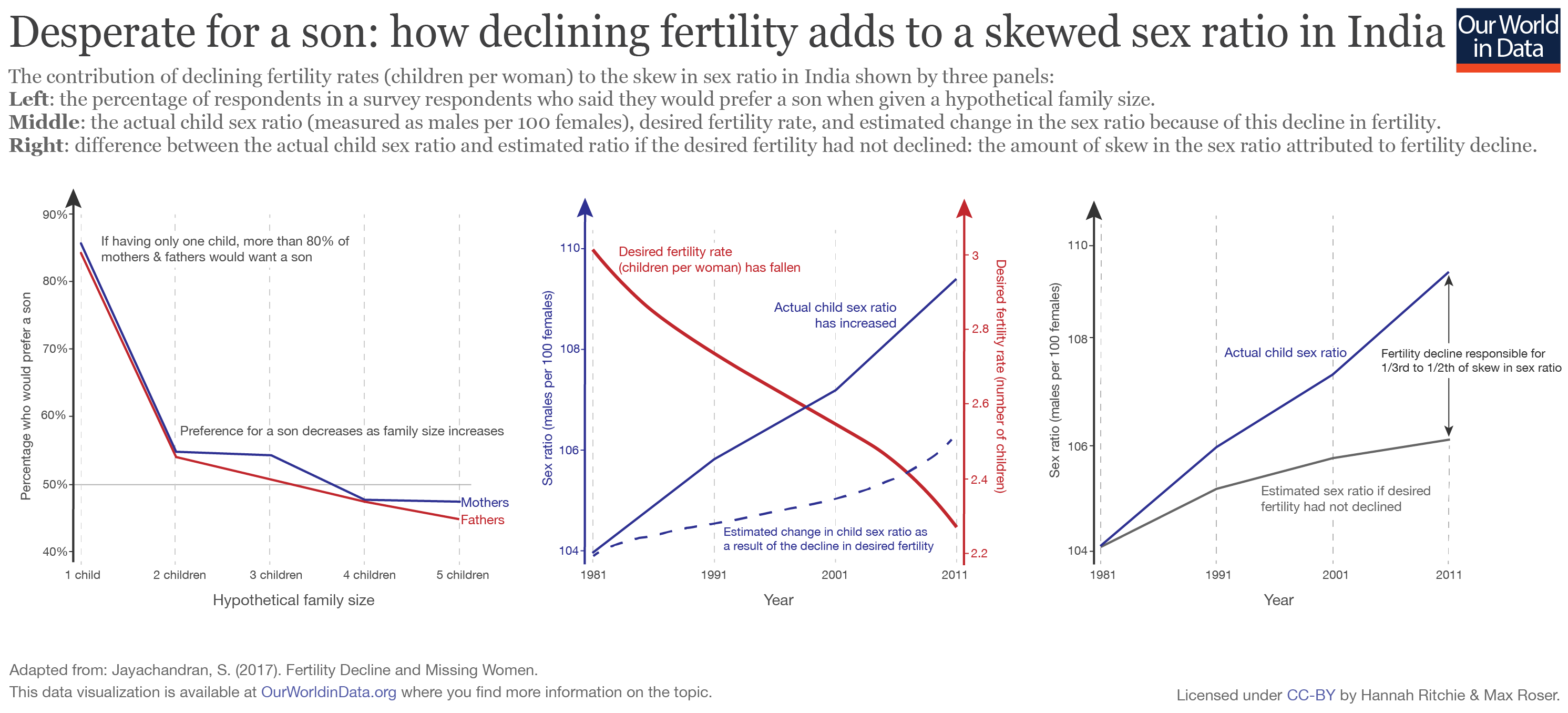

The economist Seema Jayachandran in 2017 tried to quantify how much of the skew in the sex ratio in India might be attributed to the decline of the fertility rate in the country.71

In this visualization, we summarize the results from this research, through three charts:

- Left chart: We see the percentage of respondents of a survey in India who said they would prefer a son when given a hypothetical family size (number of children) from one to five i.e. having only one child, two children etc.72 Here we see that if they were having only one child, more than 80% of both mothers and fathers would prefer a son. This preference rapidly declines when they are asked about additional children — in fact, in the scenarios in which parents already have some sons, parents preferred to have daughters.73 These results suggest that parents have a very strong preference to have a son if they have a small family.

- Middle chart: In red, we see that the desired fertility rate — the number of children a woman desires to have — has declined in India in recent decades. At the same time, the child sex ratio — the number of males per 100 females — increased. The dashed line here shows the estimated change in sex ratio which results from falling fertility rates alone.

- Right chart: the blue line shows how the child sex ratio has increased over time. Shown in grey is the estimated increase in the sex ratio which can be attributed solely to the decline in fertility rates.

The results from this study suggest that between one-third and one-half of the change in sex ratio in India since 1981 can be attributed to the decline in fertility rates.

In other words, if there had been no change in fertility rates over time, there would still be a skew in the sex ratio. But fertility declines have significantly increased son preference.

Development drives factors that can both increase and decrease sex preference

It’s difficult to come to an overall conclusion on how development affects the sex ratio. This is because better education and rising incomes can affect gender selection in different ways.

This is because the skewed sex ratio results from sex preference and the ability to act on it — by having a sex-selective abortion, for example.

Research by Kashyap and Villavicencio (2016) suggests that sex-selection practices result from three conditions being met:74

- The willingness to consider sex selection because you have a sex preference;

- The ability to act upon it through access to prenatal sex-determination screening and abortion services;

- The readiness to act upon it to get the desired sex preferences within the family.

These three conditions can change in different ways with development, education and rising incomes.

For example, research results suggest that parents with more education have a lower preference for a son.71 But, increased education is also related to falling fertility rates, and this decline in fertility increases son preference (“the fertility squeeze”).

Education therefore has two opposing effects on the sex ratio — it reduces the willingness for sex preference, but increases the readiness to change the sex of the child.

Development also affects condition the ability to act upon sex preference.

It is often the case that richer, urban families have greater access to technologies that would allow for sex identification during pregnancy, and also a safer abortion.

Poorer families in rural areas may not have this opportunity, despite having strong son preference. As they get richer, these opportunities may become available to them.

In their research, Kashyap and Villavicencio tried to model how the changes in willingness, ability, and readiness all affect the change in sex ratio in specific countries.74

They found that even very low levels of son preference can have a significant impact on the sex ratio if sex-selection technology diffuses steadily across the population and fertility declines quickly.

This means that in contexts where economic development is fast — meaning fertility rates fall quickly and prenatal screening technologies become widely accessible — even very small levels of son preference across a population can have a significant impact on the overall sex ratio.

The relationship between development and sex ratio is therefore complex and non-linear: but what's clear is that an imbalanced sex ratio doesn’t quickly disappear through economic development alone.

Does banning prenatal practices reduce sex-selective abortion?

One of the three conditions for sex-selection is the ability to act upon sex preferences through access to technology.

Prenatal sex selection relies on two technologies: prenatal sex determination (the ability to determine the sex of a foetus during pregnancy) and selective abortion.

This raises the question of whether policies that aim to regulate prenatal sex determination and abortion have an impact on the prevalence of sex selection.

Several governments limited prenatal sex selection through regulation when it became clear that sex selection was common and increasing.

For example, South Korea, China and India all implemented sex-selective abortion bans. Were they successful?

Much of the literature on the topic suggests the bans alone were not effective enough to address the problem.75

Looking at how the sex ratio at birth changed pre- and post-ban in each country also does not suggest that they were very effective.

South Korea enacted a ban on prenatal sex identification in 1987–1988. At this point, the sex ratio at birth was around 110 male per 100 female births, as we see in the chart here.

Following the introduction of the ban, the sex ratio continued to increase — reaching over 115 males per 100 female births in 1990 and maintaining a high ratio through the early 1990s.

For China the evidence is similar. In 1994, China introduced a ban of prenatal sex determination, as part of its Law on Maternal and Infant Health Care.

As we see in this chart, the sex ratio at birth continued to increase after the introduction of the ban. In 1993 the ratio was 114 male per 100 female births. By the early 2000s, it had increased to 118:100.

India introduced the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act (PNDT) in 1994 which prohibited sex selection practices, including pre-screening to determine the sex of a fetus. In the decade which followed the introduction of the act, the sex ratio at birth did not improve.

At first glance, this data would suggest that the banning of sex-selection practices was unsuccessful. The sex ratio continued to increase after their implementation.

But, while can see that bans were not effective enough to stop the practice on their own, many researchers acknowledge that we don't know the counterfactual scenario without a ban.76 In other words, without a ban, the sex ratio might have increased even further.

Some research has argued that bans were effective in preventing a worsening of gender imbalance, even if they didn't reduce it.77

These policies may have had some impact on reducing the increase, but they clearly did not come close to ending the practice.

Endnotes

Pryzgoda, J., & Chrisler, J. C. (2000). Definitions of gender and sex: The subtleties of meaning. Sex Roles, 43(7-8), 553-569.

The UN reports that only 16 and 25 percent of international migrants to Oman and UAE, respectively, were female.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). International Migration Report 2017 (ST/ESA/SER.A/403).

Orzack, S. H., Stubblefield, J. W., Akmaev, V. R., Colls, P., Munné, S., Scholl, T., … & Zuckerman, J. E. (2015). The human sex ratio from conception to birth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(16), E2102-E2111.

In the paper the authors differentiate between "karyotypically normal" and "karyotypically abnormal". This refers to whether there are mutations in chromosomes, such as an extra, missing or irregular portion of chromosomal DNA. "Karyotypically abnormal" embryos have a lower probability of surviving to birth, or often lead to other human diseases/conditions.

Jaitley, A. (2018). Economic Survey 2017-18: Volume I, Chapter 7: Gender and Son Meta-Preference: Is Development Itself an Antidote?

Gellatly, C., & Petrie, M. (2017). Prenatal sex selection and female infant mortality are more common in India after firstborn and second-born daughters. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 71(3), 269-274.

Manchanda, S., Saikia, B., Gupta, N., Chowdhary, S., & Puliyel, J. M. (2011). Sex ratio at birth in India, its relation to birth order, sex of previous children and use of indigenous medicine. PLoS One, 6(6), e20097.

Jiang, Q., Yu, Q., Yang, S., & Sánchez-Barricarte, J. J. (2017). Changes in sex ratio at birth in China: a decomposition by birth order. Journal of Biosocial Science, 49(6), 826-841.

Clarke, J., & Price, R. (1786). XVII. Observations on some causes of the excess of the mortality of males above that of females. By Joseph Clarke, MD Physician to the Lying-in Hospital at Dublin. Communicated by the Rev. Richard Price, DDFRS in a letter to Charles Blagden, MD Sec. R. S. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, (76), 349-362.

Sawyer, C. C. (2012). Child mortality estimation: estimating sex differences in childhood mortality since the 1970s. PLoS Medicine, 9(8), e1001287.

Naeye, R. L., Burt, L. S., Wright, D. L., Blanc, W. A., & Tatter, D. (1971). Neonatal mortality, the male disadvantage. Pediatrics, 48(6), 902-906.

This is also the explanation reported by the World Health Organization: "Newborn girls have a biological advantage in survival over newborn boys. They have lesser vulnerability to perinatal conditions (including birth trauma, intrauterine hypoxia and birth asphyxia, prematurity, respiratory distress syndrome and neonatal tetanus), congenital anomalies, and such infectious diseases as intestinal infections and lower respiratory infections."

Orzack, S. H., Stubblefield, J. W., Akmaev, V. R., Colls, P., Munné, S., Scholl, T., Steinsaltz, D., & Zuckerman, J. E. (2015). The human sex ratio from conception to birth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(16). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1416546112 Peelen, M. J. C. S., Kazemier, B. M., Ravelli, A. C. J., De Groot, C. J. M., Van Der Post, J. A. M., Mol, B. W. J., Hajenius, P. J., & Kok, M. (2016). Impact of fetal gender on the risk of preterm birth, a national cohort study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 95(9), 1034–1041. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12929 Zeitlin, J. (2002). Fetal sex and preterm birth: Are males at greater risk? Human Reproduction, 17(10), 2762–2768. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/17.10.2762

Boys are also more likely to be stillborn.

Mondal, D., Galloway, T. S., Bailey, T. C., & Mathews, F. (2014). Elevated risk of stillbirth in males: Systematic review and meta-analysis of more than 30 million births. BMC Medicine, 12(1), 220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0220-4

Zeitlin, J., Saurel-Cubizolles, M. J., de Mouzon, J., Rivera, L., Ancel, P. Y., Blondel, B., & Kaminski, M. (2002). Fetal sex and preterm birth: are males at greater risk?. Human Reproduction, 17(10), 2762-2768.

Carlsen, F., Grytten, J., & Eskild, A. (2013). Changes in fetal and neonatal mortality during 40 years by offspring sex: A national registry-based study in Norway. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-101

Fottrell, E., Osrin, D., Alcock, G., Azad, K., Bapat, U., Beard, J., Bondo, A., Colbourn, T., Das, S., King, C., Manandhar, D., Manandhar, S., Morrison, J., Mwansambo, C., Nair, N., Nambiar, B., Neuman, M., Phiri, T., Saville, N., … Prost, A. (2015). Cause-specific neonatal mortality: Analysis of 3772 neonatal deaths in Nepal, Bangladesh, Malawi and India. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 100(5), F439–F447. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-307636

Peacock, J. L., Marston, L., Marlow, N., Calvert, S. A., & Greenough, A. (2012). Neonatal and infant outcome in boys and girls born very prematurely. Pediatric Research, 71(3), 305.

Hintz, S. R., Kendrick, D. E., Vohr, B. R., Poole, W. K., Higgins, R. D., & Nichd Neonatal Research Network. (2006). Gender differences in neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely preterm, extremely‐low‐birthweight infants. Acta Paediatrica, 95(10), 1239-1248.

Jones, M., Castile, R., Davis, S., Kisling, J., Filbrun, D., Flucke, R., … & Tepper, R. S. (2000). Forced expiratory flows and volumes in infants: normative data and lung growth. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 161(2), 353-359.

Hoo, A. F., Henschen, M., Dezateux, C., Costeloe, K., & Stocks, J. (1998). Respiratory function among preterm infants whose mothers smoked during pregnancy. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 158(3), 700-705.

DiPietro, J. A., & Voegtline, K. M. (2017). The gestational foundation of sex differences in development and vulnerability. Neuroscience, 342, 4-20.

Townsel, C. D., Emmer, S. F., Campbell, W. A., & Hussain, N. (2017). Gender differences in respiratory morbidity and mortality of preterm neonates. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 5, 6.

Giefing‐Kröll, C., Berger, P., Lepperdinger, G., & Grubeck‐Loebenstein, B. (2015). How sex and age affect immune responses, susceptibility to infections, and response to vaccination. Aging Cell, 14(3), 309-321.

Although most genes on one X chromosome in females are inactivated, during “X chromosome inactivation”, some genes escape this inactivation. In addition, different cells may inactivate different X chromosomes, meaning that females could have a more diverse and potentially more responsive immune system compared to males.

Markle, J. G., & Fish, E. N. (2014). SeXX matters in immunity. Trends in Immunology, 35(3), 97-104.

Libert, C., Dejager, L., & Pinheiro, I. (2010). The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nature Reviews Immunology, 10(8), 594.

Libert, C., Dejager, L., & Pinheiro, I. (2010). The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nature Reviews Immunology, 10(8), 594.

Del Vecchio, C., Verrilli, F., & Glielmo, L. (2018). When sex matters: a complete model of X-linked diseases. International Journal of General Systems, 47(6), 549-568.

Fischer, J., Jung, N., Robinson, N., & Lehmann, C. (2015). Sex differences in immune responses to infectious diseases. Infection, 43(4), 399-403.

Chao, F., Gerland, P., Cook, A.R., Alkema, L. (2019). Systematic assessment of the sex ratio at birth for all countries and estimation of national imbalances and regional reference levels. PNAS.

Note that this does not imply that other countries do not have male preference or some evidence of a skewed sex ratio. Results of the Chao et al. (2019) study highlight those with the strongest statistical evidence of this imbalance.

Sen, Amartya (20 December 1990). More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing. New York Review of Books. 37 (20).

Oster, E. (2005). Hepatitis B and the Case of the Missing Women. Journal of Political Economy, 113(6), 1163-1216.

Oster, E., Chen, G., Yu, X., & Lin, W. (2010). Hepatitis B does not explain male-biased sex ratios in China. Economics Letters, 107(2), 142-144.

Lin, M. J., & Luoh, M. C. (2008). Can hepatitis B mothers account for the number of missing women? Evidence from three million newborns in Taiwan. American Economic Review, 98(5), 2259-73.

Monica Das Gupta, Can Biological Factors Like Hepatitis B Explain the Bulk of Gender Imbalance in China? A Review of the Evidence, The World Bank Research Observer, Volume 23, Issue 2, Fall 2008, Pages 201–217.

Madan, K., & Breuning, M. H. (2014). Impact of prenatal technologies on the sex ratio in India: an overview. Genetics in Medicine, 16(6), 425.

Sharma, B. R., Gupta, N., & Relhan, N. (2007). Misuse of prenatal diagnostic technology for sex-selected abortions and its consequences in India. Public Health, 121(11), 854-860.

Correspondent, L. I. (1983). Misuse of amniocentesis. Lancet, 321, 812-813.

Ramanamma, A., & Bambawale, U. (1980). The mania for sons: an analysis of social values in South Asia. Social Science & Medicine. Part B: Medical Anthropology, 14(2), 107-110.

Tandon SL, Sharma R. (2006). Female foeticide and infanticide in India: an analysis of crimes against girl children. International Journal of Criminal Justice Science.

Shi, Y., & Kennedy, J. J. (2016). Delayed registration and identifying the “missing girls” in China. The China Quarterly, 228, 1018-1038.

Cai, Y. (2017). Missing Girls or Hidden Girls? A Comment on Shi and Kennedy's “Delayed Registration and Identifying the "Missing Girls" in China”. The China Quarterly, 231, 797-803.

Moseley, K. L. (1985). The history of infanticide in Western society. Issues in Law & Medicine, 1, 345.

Levittan, M. (2012). The history of infanticide: exposure, sacrifice, and femicide. Violence and Abuse in Society. Understanding a Global Crisis. Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 83-130.

Williamson, Laila (1978). "Infanticide: an anthropological analysis". In Kohl, Marvin (ed.). Infanticide and the Value of Life. NY: Prometheus Books. pp. 61–75.

Hausfater, G., & Hrdy, S. B. (2017). Infanticide: comparative and evolutionary perspectives. Routledge.

Scott, E. (2017, June). Unpicking a myth: the infanticide of female and disabled infants in antiquity. In TRAC 2000: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Theoretical Archaeology Conference. London 2000 (p. 143). Oxbow Books.

This of course introduces uncertainty as to how good an analog modern hunter-gatherers are to prehistoric societies. Modern hunter-gatherer societies may have some contact and transfer with external influence. As a result, researchers often focus on societies with as little external influence as possible, for example having no nutritional, health, sanitation or technology transfer.

Birdsell, Joseph, B. (1986). "Some predictions for the Pleistocene based on equilibrium systems among recent hunter gatherers". In Lee, Richard & Irven DeVore (ed.). Man the Hunter. Aldine Publishing Co. p. 239.

Hill, K., Hurtado, A. M., & Walker, R. S. (2007). High adult mortality among Hiwi hunter-gatherers: Implications for human evolution. Journal of Human Evolution, 52(4), 443-454.

Divale, W. T. (1972). Systemic population control in the middle and upper palaeolithic: Inferences based on contemporary hunter‐gatherers. World Archaeology, 4(2), 222-243.

Langer, W. L. (1974). Infanticide: A historical survey. The Journal of Psychohistory, 1(3), 353.

Milner, Larry S. (2000). Hardness of Heart / Hardness of Life: The Stain of Human Infanticide. Lanham/New York/Oxford: University Press of America.

Hughes, A. L. (1981). Female infanticide: Sex ratio manipulation in humans. Ethology and Sociobiology, 2(3), 109-111.

Kellum, B. A. (1974). Infanticide in England in the later Middle Ages. The Journal of Psychohistory, 1(3), 367.

Cecilia Lai‐wan, C., Eric, B., & Celia Hoi‐yan, C. (2006). Attitudes to and practices regarding sex selection in China. Prenatal Diagnosis: Published in Affiliation With the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, 26(7), 610-613.

Porter, T., & Gavin, H. (2010). Infanticide and neonaticide: a review of 40 years of research literature on incidence and causes. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 11(3), 99-112.

Chunkath, S. R., & Athreya, V. B. (1997). Female infanticide in Tamil Nadu: some evidence. Economic and political weekly, WS21-WS28.

Lee, B. J. (1981). Female infanticide in China. Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques, 163-177.

Million Death Study Collaborators. (2010). Causes of neonatal and child mortality in India: a nationally representative mortality survey. The Lancet, 376(9755), 1853-1860.

Raj, A., McDougal, L. P., & Silverman, J. G. (2015). Gendered effects of siblings on child malnutrition in South Asia: cross-sectional analysis of demographic and health surveys from Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(1), 217-226.

Aurino, E. (2017). Do boys eat better than girls in India? Longitudinal evidence on dietary diversity and food consumption disparities among children and adolescents. Economics & Human Biology, 25, 99-111.

Jayachandran, S., & Kuziemko, I. (2011). Why do mothers breastfeed girls less than boys? Evidence and implications for child health in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(3), 1485-1538.

Ghosh, N., Chakrabarti, I., Chakraborty, M., & Biswas, R. (2013). Factors affecting the healthcare-seeking behavior of mothers regarding their children in a rural community of Darjeeling district, West Bengal. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health, 3(1).

Barcellos, S. H., Carvalho, L. S., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2014). Child gender and parental investments in India: Are boys and girls treated differently?. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(1), 157-89.

Bharadwaj, P., & Lakdawala, L. K. (2013). Discrimination begins in the womb: Evidence of sex-selective prenatal investments. Journal of Human Resources, 48(1), 71-113.

Sen, A. (1990). More than 100 million women are missing. The New York Review of Books, 37(20), 61-66.

Bongaarts, J., & Guilmoto, C. Z. (2015). How many more missing women? Excess female mortality and prenatal sex selection, 1970–2050. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 241-269.

Bongaarts, J., & Guilmoto, C. Z. (2015). How many more missing women? Excess female mortality and prenatal sex selection, 1970–2050. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 241-269.

Hesketh, T., Lu, L., & Xing, Z. W. (2011). The consequences of son preference and sex-selective abortion in China and other Asian countries. CMAJ, 183(12), 1374-1377.

Das Gupta, M., Zhenghua, J., Bohua, L., Zhenming, X., Chung, W., & Hwa-Ok, B. (2003). Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea. The Journal of Development Studies, 40(2), 153-187.

Diamond‐Smith, N., Luke, N., & McGarvey, S. (2008). "Too many girls, too much dowry": son preference and daughter aversion in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 10(7), 697-708.

Puri, S., Adams, V., Ivey, S., & Nachtigall, R. D. (2011). “There is such a thing as too many daughters, but not too many sons”: A qualitative study of son preference and fetal sex selection among Indian immigrants in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 72(7), 1169-1176.

Tandon, S. L., & Sharma, R. (2006). Female Foeticide and Infanticide in India: An Analysis of Crimes against Girl Children. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 1(1).

Hesketh, T. (2011). Selecting sex: The effect of preferring sons. Early Human Development, 87(11), 759-761.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2007). Sex-ratio imbalance in Asia: Trends, consequences and policy responses. Paris: LPED/IRD.

Hudson, V. M., & Den Boer, A. (2005). Missing women and bare branches: gender balance and conflict. Environmental Change and Security Program Report, (11), 20-24.

Diamond-Smith, N., & Rudolph, K. (2018). The association between uneven sex ratios and violence: Evidence from 6 Asian countries. PLoS One, 13(6), e0197516.

Filmer, D., Friedman, J., & Schady, N. (2008). Development, modernization, and son preference in fertility decisions. The World Bank.

Gupta, M. D. (1987). Selective discrimination against female children in rural Punjab, India. Population and Development Review, 13(1), 77-100.

To calculate this, we need to calculate the probability that in having 5 children, we have five girls. Because the "natural" sex ratio at birth is around 105 boys per 100 girls, the probability of having a girl at each birth is slightly lower than half: it's around 47.6%. To calculate the probability of having 5 girls, we then do 0.476^5 = 0.0245 [or 2.45%]. The probability that you have at least one boy is therefore 100% - 2.45% = 97.6%.

Since the "natural" sex ratio at birth is around 105 boys per 100 girls, the odds of having a boy are slightly higher than having a girl: 52%. To calculate the odds of having a boy when you have two children, we start by calculating the probability of having two girls. The probability of having a girl at each birth is 47.6% [100/105 * 100]. The probability of two births producing two girls is then calculated as 0.476^2 = 0.227 [22.7%]. The odds that one is a boy is therefore 100% - 22.7% = 77%.

Jayachandran, S. (2017). Fertility decline and missing women. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(1), 118-39.

The survey was actually posed to mothers and fathers of what they would want for their own children (who were all in secondary school at the time of the of survey). Asking it of a future hypothetical scenario helps to avoid hindsight bias.

The reason for a switch to daughters is not totally clear. It's suggested having daughters within larger families is preferred to provide care for others in the family and the household. It may also be the case that a larger number of sons creates tension and conflict with regards to resource allocation.

Kashyap, R., & Villavicencio, F. (2016). The dynamics of son preference, technology diffusion, and fertility decline underlying distorted sex ratios at birth: A simulation approach. Demography, 53(5), 1261-1281.

Gupta, M. D. (2016). Is banning sex-selection the best approach for reducing prenatal discrimination?. In Population Association of America meeting, Washington DC.

Subramanian, S. V., & Selvaraj, S. (2009). Social analysis of sex imbalance in India: before and after the implementation of the Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PNDT) Act. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63(3), 245-252.

Gupta, M. D. (2016). Is banning sex-selection the best approach for reducing prenatal discrimination?. In Population Association of America meeting, Washington DC.

Nandi, A., & Deolalikar, A. B. (2013). Does a legal ban on sex-selective abortions improve child sex ratios? Evidence from a policy change in India. Journal of Development Economics, 103, 216-228.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2019) - “Gender Ratio” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/gender-ratio' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-gender-ratio,

author = {Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser},

title = {Gender Ratio},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2019},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/gender-ratio}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.